Today, I want to focus on one narrow topic raised by a contributor to Shakmatnyye Kollektsionery: what is a Grandmaster set and what are the differences between the different types of Grandmaster sets mentioned by collectors?

A Grandmaster, or Grossmeister set is most generally a set that was used at the highest levels of Soviet chess, that is, by Grandmasters. Soviet sets typically did not have names, just as most Soviet consumer products did not have brand names. Instead, chess sets were described by functional categories.

Grandmaster sets were used by grandmasters. Tournament sets were for use generally in tournaments. Yunost sets were for students and youth. In Xadrez Memoria, Arlindo describes these GM, or Grandmaster, sets as:

Soviet pieces characteristic of many Clubs, competitions and even simple chess lovers that in a park, or Garden, anywhere in the former Soviet Union used to use them. Almost always these pieces were made with the respective folding board that also served as a box where they were kept (such “anemic” trays of 4.5 – 5cm square for pieces with a King base with 3.5-4 cm!… All of these pieces are very reasonable in size, with the KINGS walking 10-11 cm high… [T]hey are very different sets from each other and have been used in different times… .

Xadrez Memoria, 4 December 2012.

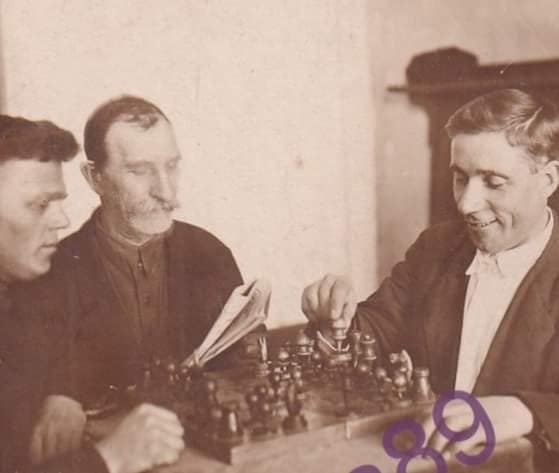

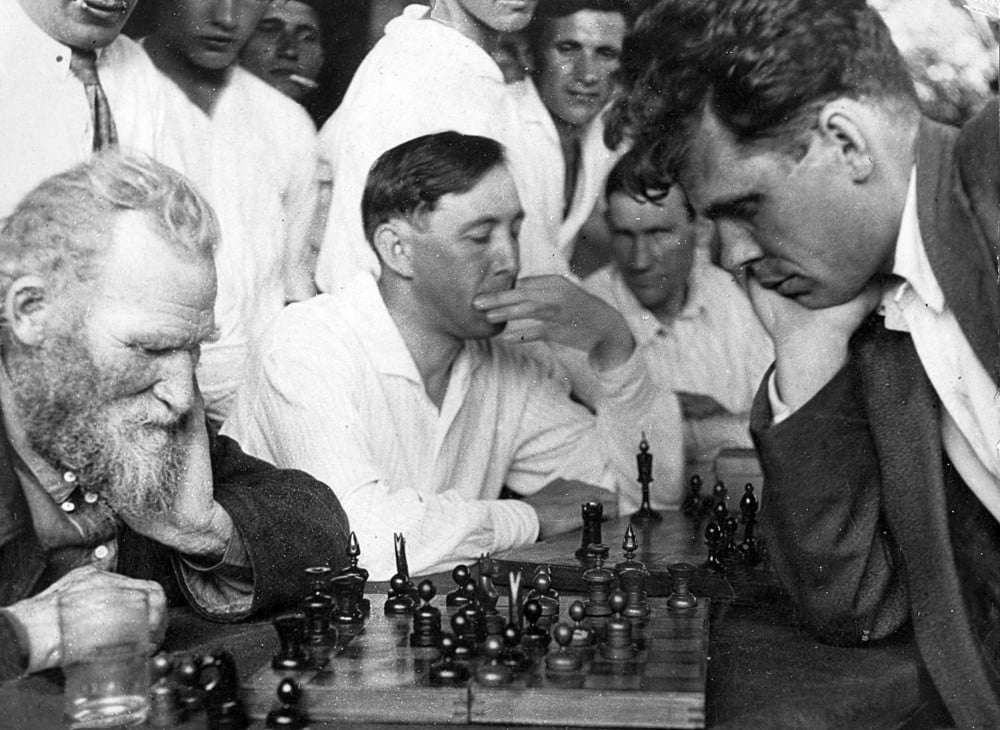

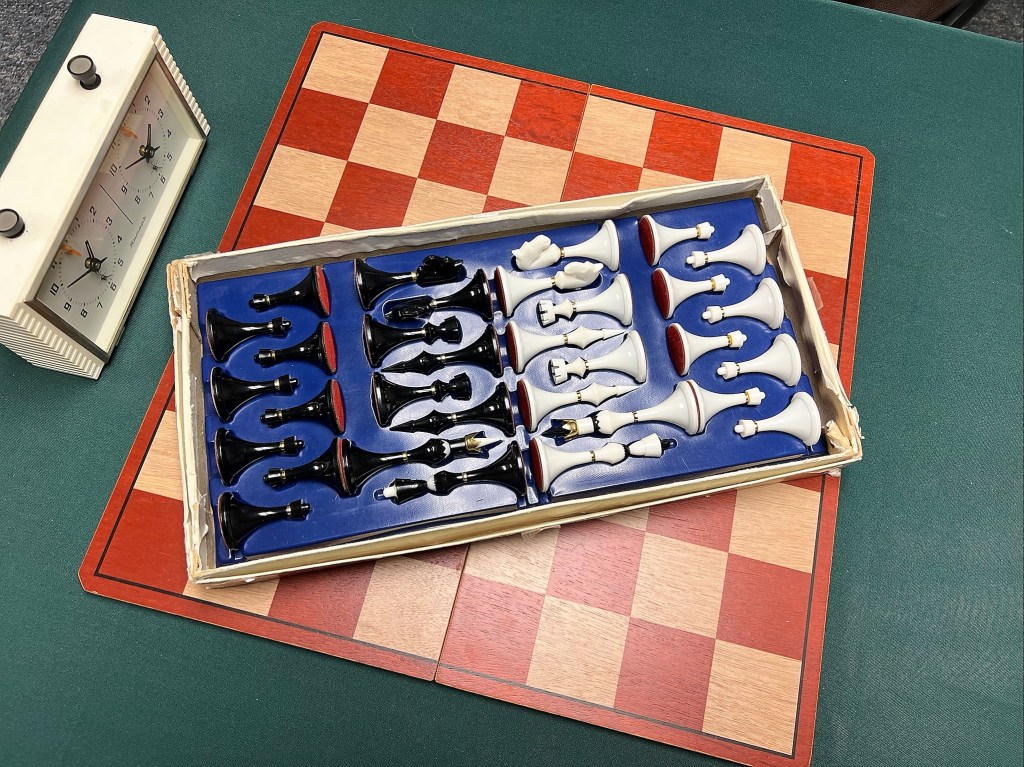

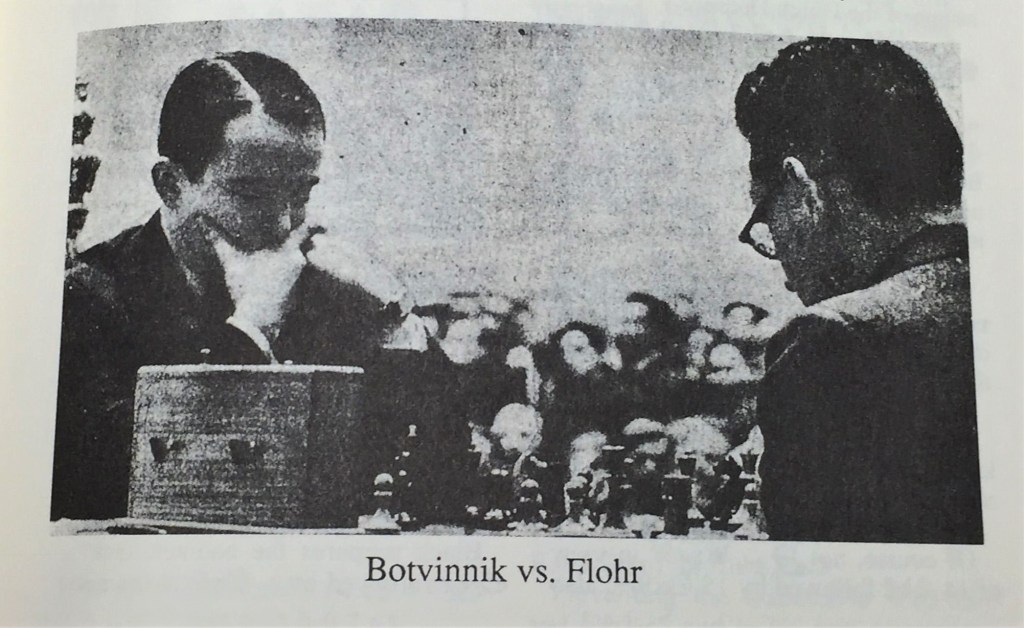

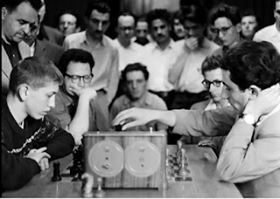

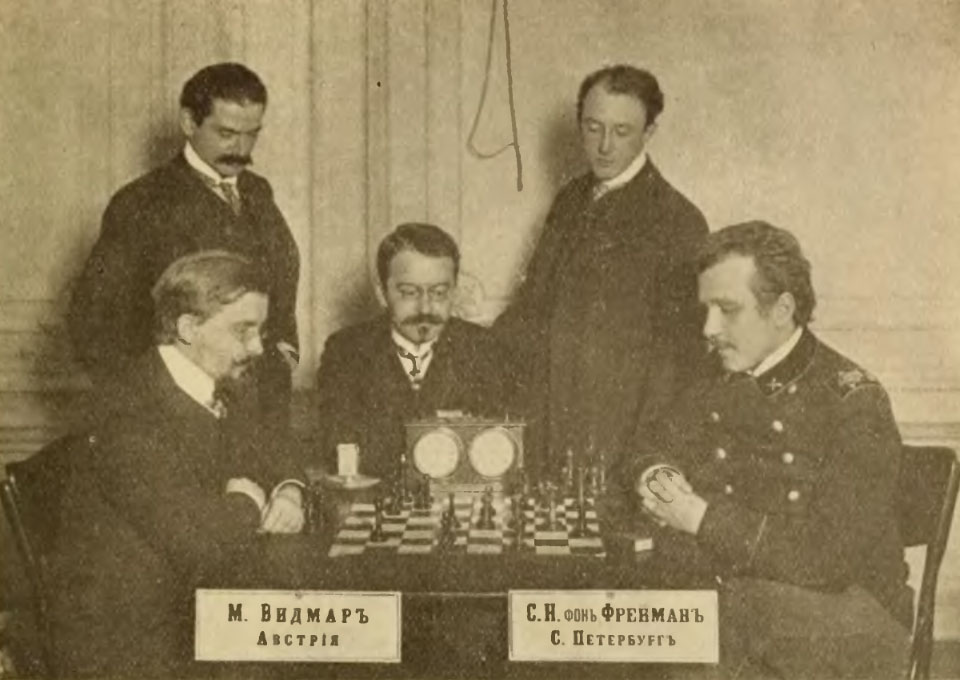

Vieira designates each type of Grandmaster set with a number, 1-4, and dedicates one sub-section of his video to each GM type. He dates the GM1 in the seventies and eighties; the GM2 in the sixties through the eighties; the GM3 goes undated in both the video and the blog; The GM4 is undated, but he describes it as “the last version of this competitive set,” and shows it in use in the mid-eighties. The photographic record provides evidence that each of the four types indeed were used at the highest levels of Soviet Chess.

Within each GM category, there were a number of different sets sharing the same basic style. Some of the differences can be attributed to when or where they were produced, others by the intended audience. Thus each style had better made and finished types that were used at the high levels, and simplified versions that were mass marketed to the millions who played chess. Over the course of four articles, we will examine each of Arlindo’s four types.

Grandmaster 1 Pieces

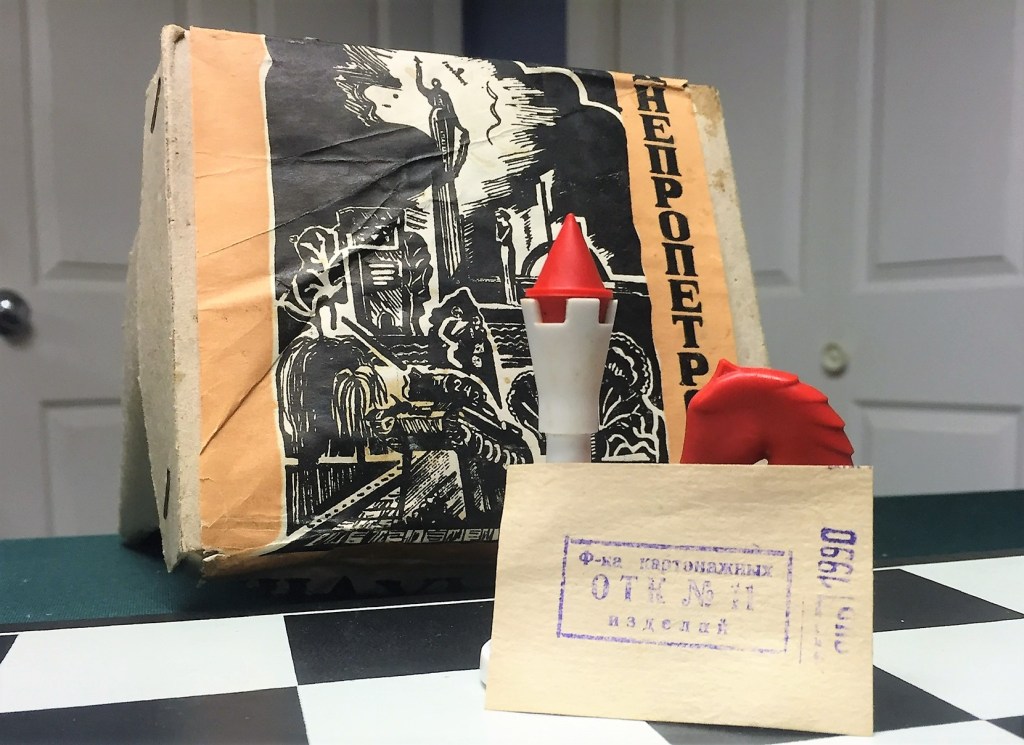

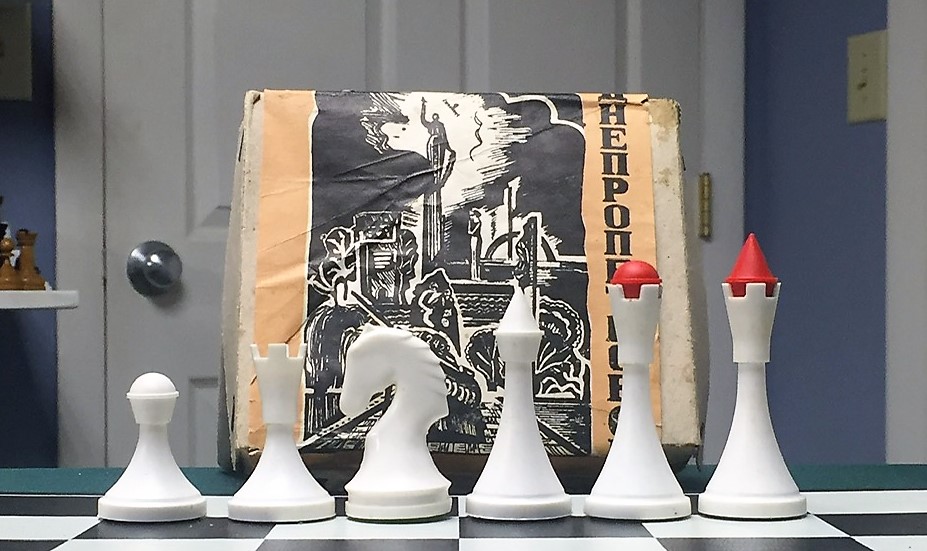

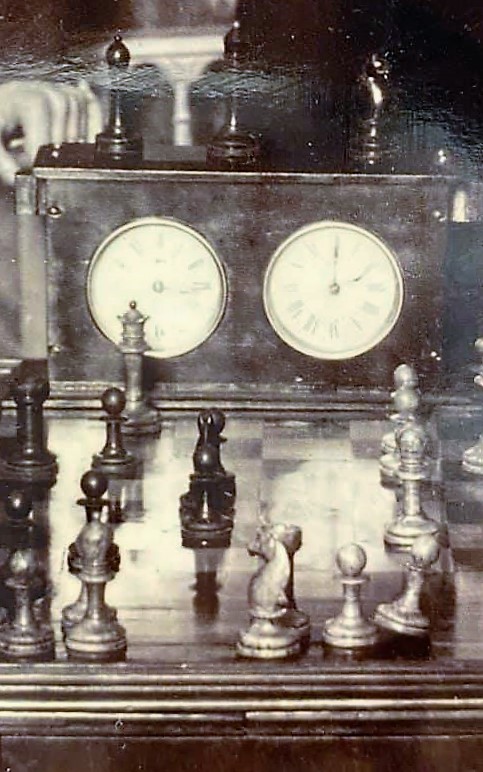

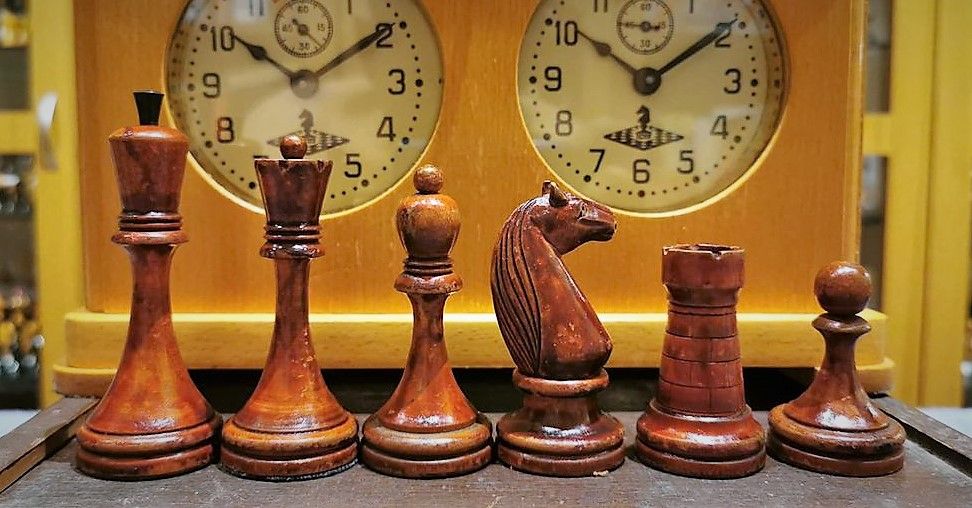

Chuck Grau Collection, photo.

Figures 1 and 2 present an example of a GM1 set from the 1960s. They are obviously well-used, not surprising insofar as Vieira describes the GM1 to have been “very popular in chess clubs.” In some ways, this set represents the end product of Soviet design. Reminiscent of a simplified BFII design, the GM1 incorporated what I call the Voronezh Curve, extending up from the base, forming a stem concave in shape, which blossoms out to form the pedestal upon which the piece signifiers rest.

The Royals’ crowns are bounded by a simple band, rather than the three-piece (two collars and a connecting area), with a simple trapezoidal shape, slightly domed at the top of the king. The coronets, miters, and turrets all lack details. The bishop’s miter has simplified the common Soviet onion dome to the shape of a tear. The knight is basically a slab with cuts across the vertical plane, and carvings cut into the wood. Its shape is an almost an exaggeration of the standard Soviet CV shape. All of the simplifications retain their Soviet character while facilitating mass production of the pieces. It is a simple design, perfect for mass production. The stem rises almost seamlessly from the base, forming a concave curve that trumpets out to serve as a pedestal, upon which the piece signifier–crown, coronet, miter, or ball–rests. The finials atop the king and queen are made of wood. In later versions, they are made of plastic. The queen’s coronet bears no crenellations. The knights are quite simple, comprising a slab with two angular cuts signifying the mane. The knight’s back forms a simple C-Curve, whereas the chest is cut to an angular V. The back of the ears continue the upward line of the back. The bishop’s miter is a simple tear-shape without a cut. The rook’s turret lacks merlons.

According to St. Petersburg Collector Sergey Kovalenko, many of these sets were made in Oredezh settlement, Luga district, Leningrad region.

Sergey has compiled a history of chess set production in Oredezh/Luga:

GM1 chessmen. Oredezhsky DOZ. Oredezh settlement, Luga district, Leningrad region.

The factory produced chess sets (board and pieces), as well as chess boards and tables separately. Boards of at least four sizes – 20×20 cm, 30×30 cm, 40×40 cm, 45 x45 cm.

“GM1″ was produced in at least three sizes– for a board of 30cm, 40cm and 45cm.

From about 1960 to 1966, white figures and boards were covered with a red-brown varnish (most likely based on alcohol), from about 1967 they switched to a colorless nitrocellulose varnish.

In the 1970s, the finals began to be made plastic. In the “best” years, in the mid-70s, [the] factory produced up to 13,000 thousand sets per month.

Chain of renaming.

The artel “УтильПром/Utilprom” (in some sources “Утиль/Util”) was established in 1948.

In 1953 it was renamed “Промвторсырье/Promvtorsyrye” (in some sources “Промвторспрос/Promvtorspros”).

In 1957, it was renamed the

“Ореджская промыслово кооперативная артель/Oredezh Promislovo-Kooperativny Artel”…In 1960 was reorganized into the “Оредежский ДОЗ/ Oredezhsky DOZ.

The Oredezhsky DOZ existed with this name until April 1970, when the Oredezh and Luga plants were merged into “Лужский ДОК/Luzhsky DOK”.

In 1982, it was renamed “Лужский ЛДОК/Luzhsky LDOK.”

“Лужский ДОЗ/Luzhsky LDOK” Luga city, Leningrad region, has its own history.

In 1946, the “Лужский Мебельщик/ Luzhsky mebelschik” artel was established.

In 1956 it was renamed the “Лужская Мебельная фабрика / Luga Furniture Factory.”

In 1962 it was renamed the “Лужский ДОЗ/Luzhsky DOZ.” …

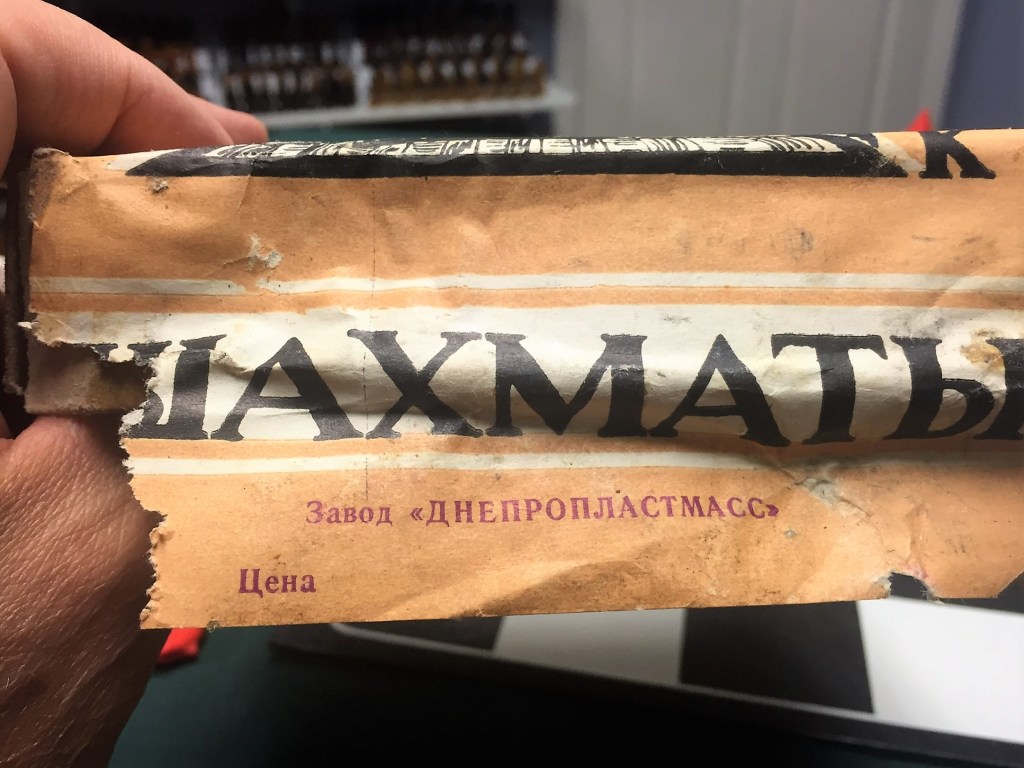

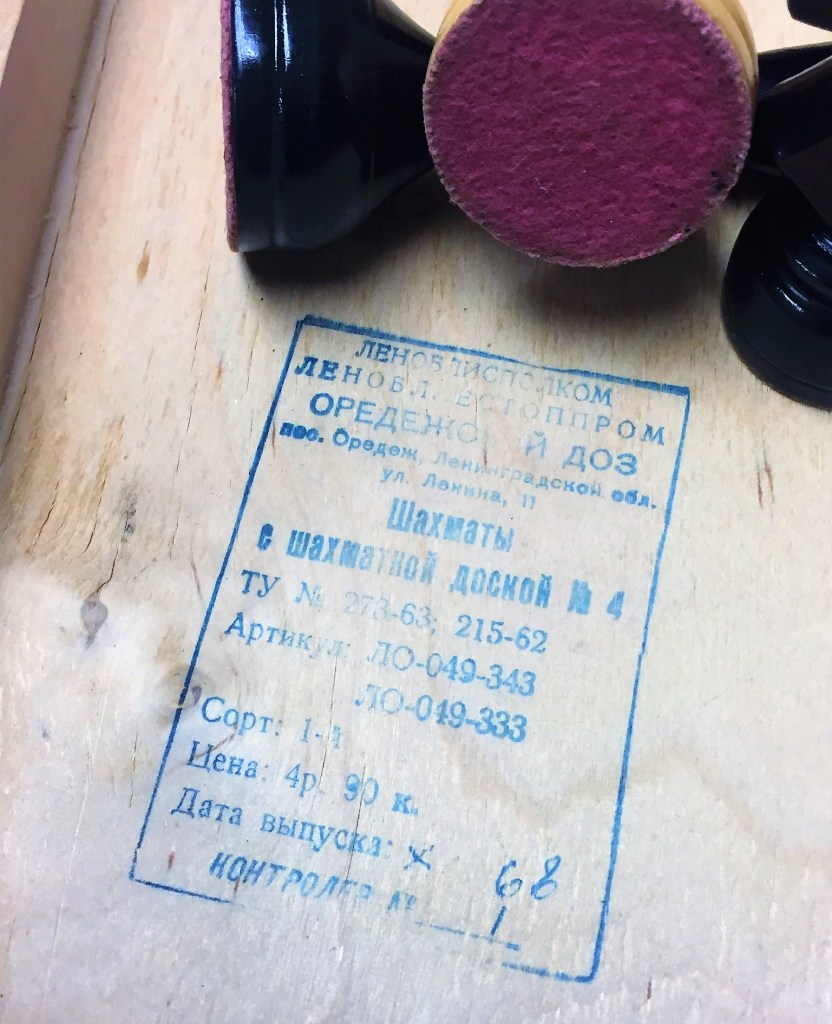

Figure 4 below shows a stamp found inside the board of a first quality set produced in 1968 in the Oredezh Wood Processing Factory, 11 Lenin Street, in Leningrad Oblast. The set included both the pieces and Board No. 4, as both are described and their product numbers given. The finials are all wood. The board’s squares are 4mm x 45mm.

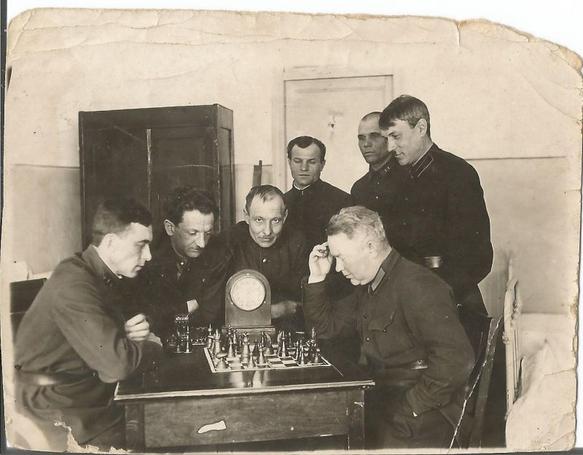

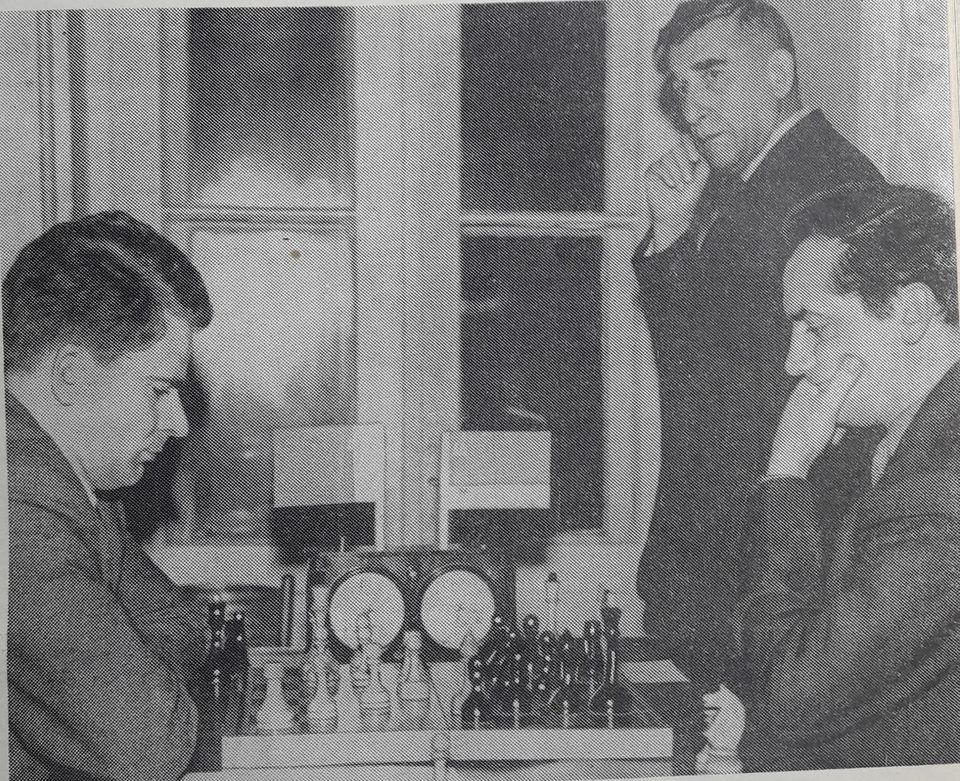

The next photo, Figure 5, gives us a rare look inside a Soviet chess factory. It depicts a chess assembler foreman inspecting GM1 pieces in the Oredezh Wood Processing Factory.

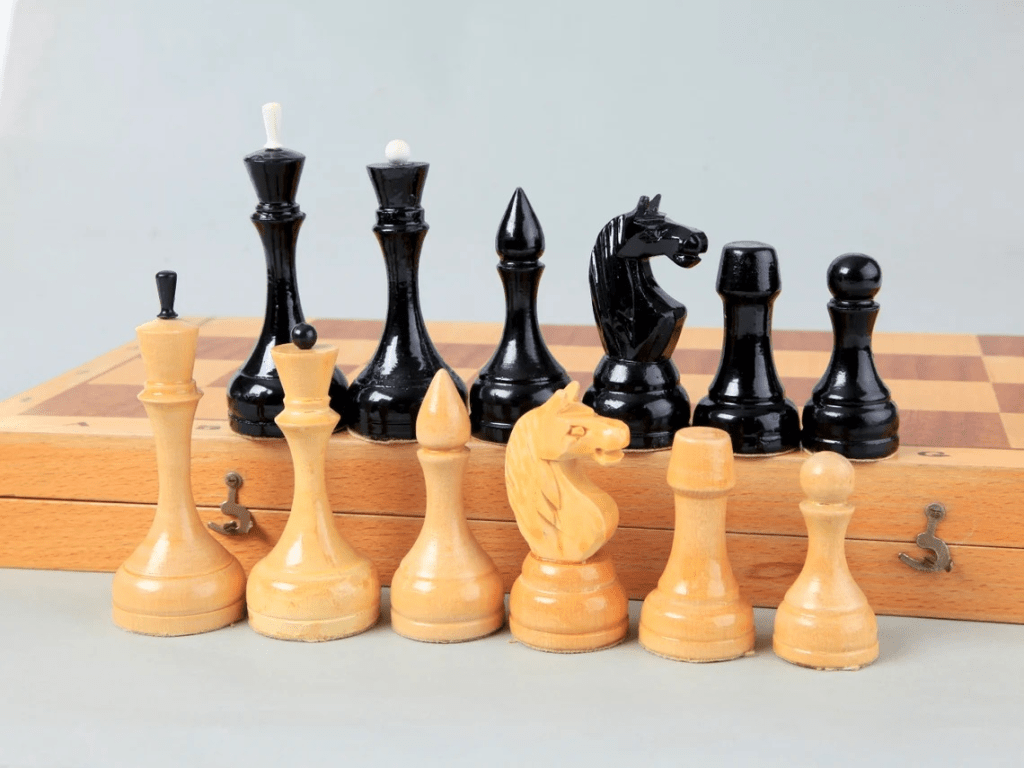

As Sergey described, the Orodezh Factory changed merged into to Luga, and began branding its sets with Luga’s distinctive round trademark, seen on the box in Figure 6. It is a late model set with all plastic finials.

Figure 7 depicts the GM1 design in an analysis-sized set with kings of 76 mm. The finials are wooden, and the knights of an early pattern. They are consistent with those Sergey described as being for a 30 mm No. 3 board.

According to Arlindo Vieira, smaller sets like these were “very popular in schools and clubs, amateur tournaments.” It is perhaps a stretch to use a classification he coined to denote sets used by grandmasters in high level tournaments to describe a miniature set, but I use it to reference the design of the pieces rather than who used them.

As Sergey noted, the plant moved from red/brown varnish to a clear coat in 1967. Here are the pieces from the 1968 set shown in Figure 4.

As of this update, collector and graphic designer Eva Silvertant is working on a typology of GM1 knights. She has identified two other styles of GM1 knights. The first is similar to those shown in Figures 1, 2, 7, 9, and 10 from the Orodezh/Luga factory.

The knights in this set appear to be very similar to those found in GM2 sets manufactured by the Perkhushkovskaya Factory of Cultural Goods, which suggests that these GM1 variants were produced there. More research is needed.

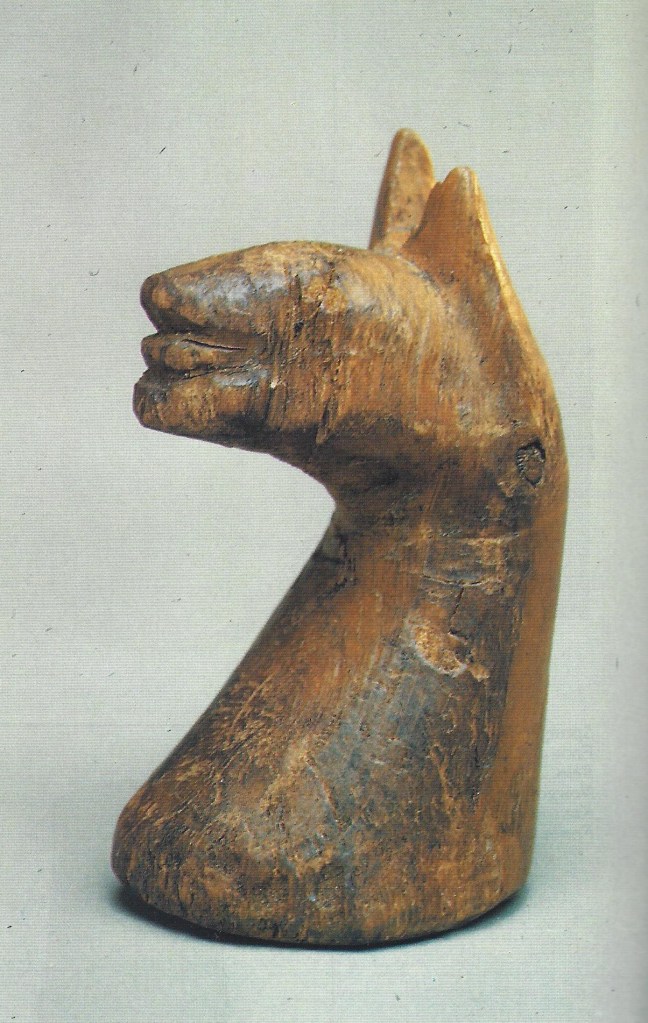

A second variant Eva has brought to our attention is what she aptly dubs the “Fox Head” Knights. She states that they were made by Luzsky Woodworking Enterprise, which Sergey had identified as the 1972 successor to Oredezhsky DOZ, renamed to essentially Eva’s form in 1982. Interestingly, these Fox Head knights appear similar to those Arlindo Vieira first posted in 2012. At this point, I am unaware of any cardboard boxes with identifying information relating to this variant.

GM1 Wolf-Ear Variant

One interesting variation of the basic GM1 design, seen in Figures 8 and 9 below, has been called the “Wolf Ear” or “Dropjaw” set in reference to its unique knights with their dropped jaws and their wolf-like ears. The knight’s wolf-like ears echo the sharp peak of the cleric’s tear-shaped miter. The rook’s lines also have been exaggerated over those of the standard GM1.

The king stands 103 mm tall with a good-sized base of 45 mm. Lightly weighted. Like other GM1 sets, the Wolf Eared ones came in a variety of sizes. Steven Kong’s collection includes one with 112 mm kings. Ribnar Mazumdar’s collection also includes a specimen with 112 mm kings.

The Wolf-Ear set retains the general shape of the standard GM1, but is heightened and widened, the severity of the stem’s curve is reduced, the knight’s ears and mouth have been exaggerated, the king’s crown has been given a larger bulge on top, the king’s and queen’s pedestals have been heightened, the connection between pedestal and crown has been increased on the royals, the king’s and queen’s finials have been shortened and reduced in diameter respectively, and the sides of the rook’s turret have been given a curve.

One significant problem with the Wolf-Ear set is that the kings and queens are difficult to distinguish. In fact, the Wolf-Ear queen looks very much like the king in other Soviet sets as well, compounding the problem. Another confusing design element is that the stem of the queen is longer than that of the king, connoting that she, not her liege, is the most important piece. Moreover, the unusual length of her stem results in her pedestal being above the kings, destroying the descending line of the pedestals that harmonizes the sight of the pieces on their initial squares and further confuses the connotation of value.

According to Sergey Kovalenko, the Wolf-Ear sets were manufactured in a correctional colony, Institution OI 92/9 in Makhachkala, DASSR (Dagestan). The colony later received the designation IK-2. The sets accompanied by the following labels were made in the 1980s.

Perhaps the unique profile of the Wolf-Ear knights derives from the Silver Wolf in the flag of the Avar Khanate of Dagestan.

GM1 Conclusion

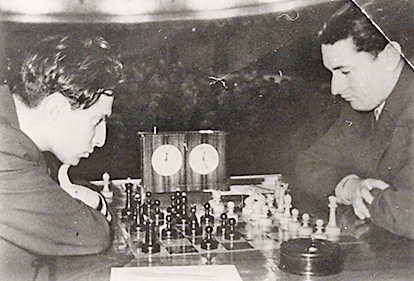

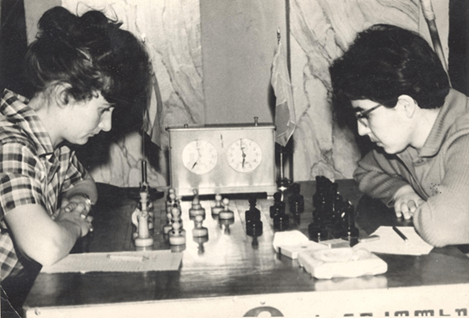

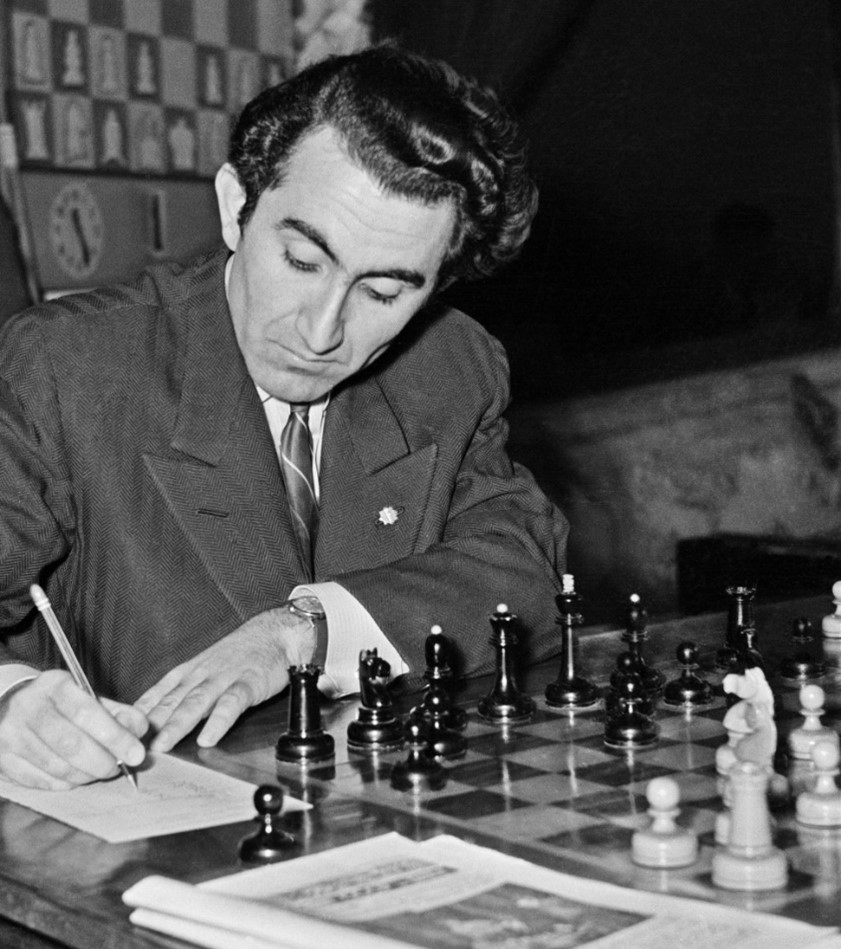

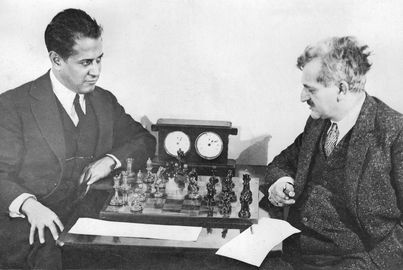

This concludes our survey of Grandmaster 1 chess pieces. Next we will turn to another very Soviet design, the Grandmaster 2 pieces, sometimes called the Bronstein pieces owing to a photo of Bronstein and Tal playing with them.

Updated 9 June 2022, 7 July 2022, 7 March 2025.