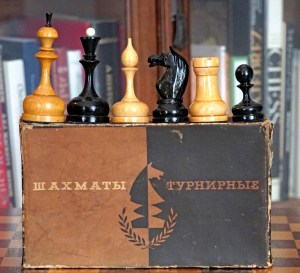

We often see a particular style of Soviet set described as “Latvian” and as “Tal’s favorite.” Although neither claim is supported by the current state of research, both contribute to ongoing misunderstanding of the set’s origin and significance.

According to Merriam-Webster.com, an Urban Legend is an often lurid story or anecdote that is based on hearsay and widely circulated as true. While there no doubt are lurid details about the life and times of Mikhail Tal, none are known to be associated with these pieces.

Both claims originate from slides appearing in Arlindo Vieira’s seminal 2012 video on Soviet and Russian chess sets and associated test in his blog Xadrez Memoria. The set appearing in the banner is the one from his collection that he claims to be Latvian. The claim that the set is Latvian arises from a slide in which Arlindo proclaims that “I call this set Latvian” and the other from a slide in which he declares that “He [Tal] loved these pieces!” The first claim rests on a questionable inference; and the basis for collectors repeating either claim is little more than hearsay.

Urban Legend 1: “These Pieces Are Latvian”

Here is the slide that collectors are ultimately relying upon when they claim that sets like Vieira’s are Latvian.

Vieira 2012 Video.

When collectors and dealers claim pieces like these are “Latvian,” they are knowingly or unwittingly referring to this slide, rather than first hand information or research actually linking the sets to Latvia. They are repeating Arlindo’s designation for the truth of the matter asserted–that they’re Latvian– making the statement relied upon hearsay.

A more defensible claim might be: “I believe this set to be Latvian and I am relying on Arlindo’s expert opinion in doing so.” If we consider Arlindo as an expert witness, as I do, we are entitled to inquire into the basis of his opinion. He lays that out in this very slide–the set was popular in Latvia, as evidenced by the many photos he found of like sets being used in Latvian events. His conclusion that the set is Latvian rests on the proposition that a set’s place of origin can be inferred from the frequency with which we find photos of players using it there. As he explains in his blog, Xadrez Memoria:

I have noticed through photos that certain games were used more frequently in the former Baltic Republics, and less, much less in tournaments in the capital or Leningrad, just to give an example. This is the case with these pieces of mine, which curiously appear in dozens and dozens of photos related to Latvian schools, tournaments and players. In fact, curiosity or not, even today at Ebay auctions, when these pieces appear, the sellers are mostly from Latvia, just like the one who sold me the pieces shown here.

On its face, this seems fairly reasonable, but the more we parse it, the less reasonable it becomes. If frequency of appearance in photos and Ebay auctions implies place of origin, what happens when photos of sets used in different venues appear? Or more sets are sold by vendors in Ukraine? The most reasonable response would be to say that the set more likely comes from the place from which the most photos and sales of it arise. We have no idea of how representative his photos and Ebay vendors are. What if, notwithstanding the photos Arlindo examined, more of the sets actually were used in Moscow. Does that make it a Moscow set? Or perhaps there actually are more photos of the set being used in Leningrad, which he missed in his review? Is it now a Leningrad set? My point is that it is not inherently reasonable to definitively infer the origin of the set from a handful of photos without considering how representative the photos are of all photos of Soviet sets in all locations. We just don’t know from the evidence presented in Arlindo’s video and website. But I think it’s fair to say that since 2012, we have examined more photos of Soviet sets in use than Arlindo did or could access back then.

I think the best way to understand Arlindo’s statement “I called this set Latvian!” is as an hypothesis, rather than a firm conclusion. He called it “Latvian” based on photos and Ebay listings he found. It’s reasonable to form an hypothesis based on such limited research. But like every other hypothesis, its validity is subject to being tested by the collection and analysis.

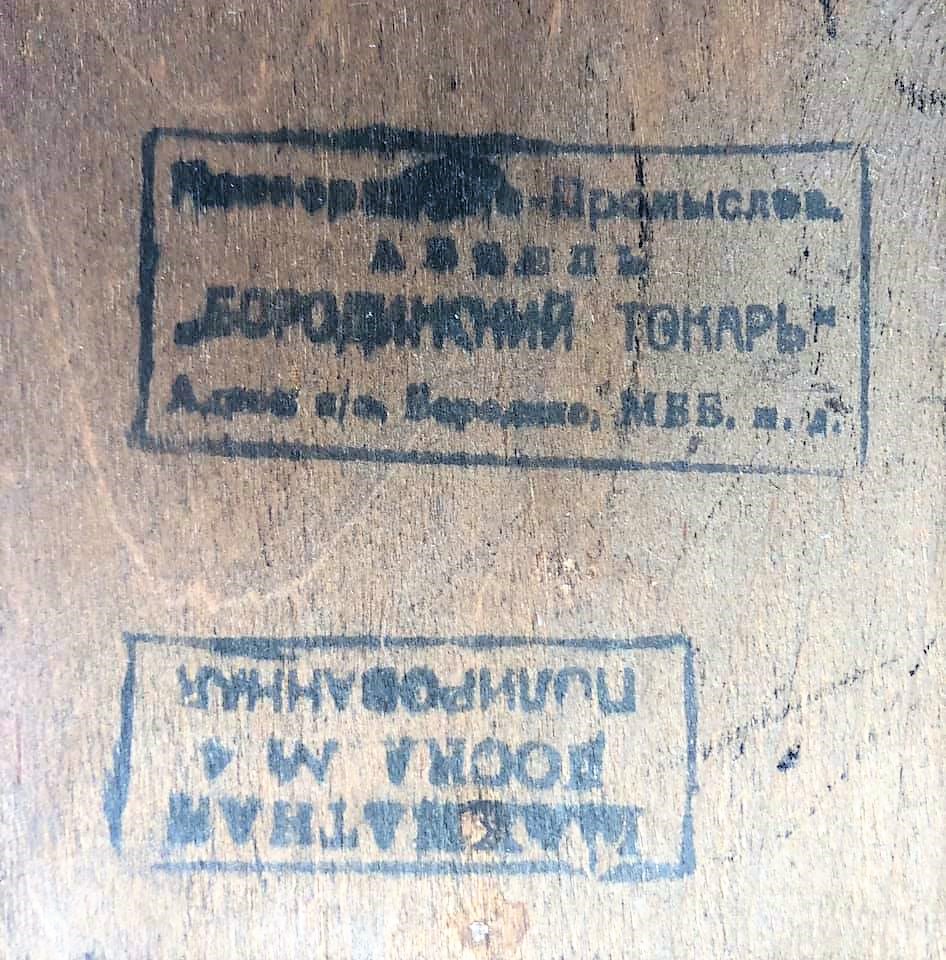

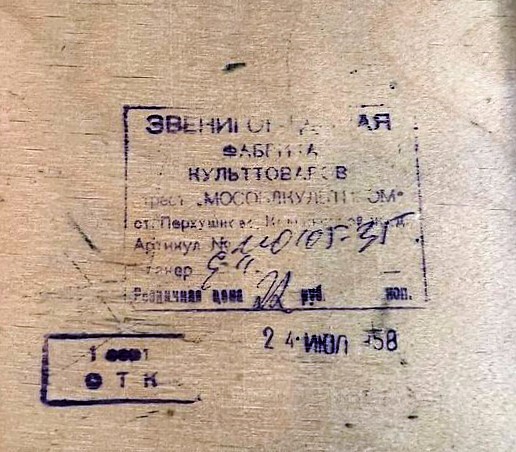

Since 2012, a great deal of data has been uncovered that overwhelmingly indicate that sets of this basic design were made in many places, but not one of them is Latvia. We find evidence of them having been made in a children’s penal colony in Siberia, in Gulags in Mordovia, artels in Khalturin and Ivanovo, and in state factories in Ivanovo and Semenov. We owe a debt of gratitude to Vladimir Volkhov for his research into the sources of production, reported in his wonderful blog, Retrorussia. And this evidence consists of much more direct evidence than photos of use. It comprises stamps and labels identifying places of origin on and in the boxes containing the actual pieces. This is hard evidence, allowing far stronger inferences than could be made in 2012 in the absence of such a rich record.

This all, of course, begs the question as to what these sets should be called. Vladimir’s solution is to adopt Russian collectors’ practice of naming sets by where they were made. So sets made in Mordovia would be called Mordovian; those in Khalturin, Khalturiskie; those in Semenov, Semenovskie; those in Ivanovo, Ob’edovskie, for the village in Ivanovo Region where the production facilities were located. I think this is a very important part of the naming solution. It incorporates and honors local practice, and ties sets to locations where they actually originated.

But I have two problems with adopting this convention as a total resolution to the naming issue. The first is that it completely ignores the important issue of style. It cannot be disputed that the “Latvian” sets from Berezovsky, Mordovia, Khalturin, Semenov, and Ivanovo are the same general style. That is an important observation, as it indicates design notions and practices transcended localities and regions, and ignoring it leaves important chapters of the story unwritten.

The second problem is that the location convention creates as much confusion as it eliminates. Take the Khalturin example. Many different styles of chess pieces were manufactured there. Under the location convention all of them would bear the same name, and we never could distinguish one from the other in writing without attaching a picture to clarify which one we were talking about. I find that unacceptable.

Ultimately, we need to accept a naming convention that recognizes both style and place of manufacture. And I would include a date, because pieces made in the same style in the same place could vary over time in some significant details. But, then, what should we call this not very Latvian design? I would be comfortable calling the style Berezovsky, in homage to the children of the Gulag who apparently first made them. I also would be comfortable calling them Everyday, in accordance with the category John Moyes found on the label of a set from Ivanov. I like two things about this option. First, it is homage to the Soviet practice of calling consumer items, including sets, by the category of intended use. Second, sets in this style were ubiquitous, truly the everyday sets of many Soviet households. Until we reach some consensus on this, I probably will continue to call the style Mordovian, as I find it the most beautiful iteration of this venerable style.

Urban Legend 2: “Tal’s Favorite Set!”

This one is a real whopper.

“Tal’s favorite set.” Mein Gott im Himmel, how do you know that?

I’ve never seen a collector or dealer asserting this claim to state his or her basis for making it, myself included. One hypothetically might have first hand knowledge: “I knew Tal, and Tal told me it was his favorite set”; or “I watched Tal play and every time he chose the set he chose this one”; or “I listened to Tal give an interview to a Filipino Grandmaster and he said it was his favorite set and that he was the victim of vast international conspiracies.” Wait, that was Fischer. Or, “I read such and such by Tal and he wrote that it was his favorite set.” Or one might have evidence from which one might infer it was his favorite, like multiple photos of Tal using the set in his residence or hotel rooms, or sitting over his mantle or displayed on a shelf.

But no, “Tal’s favorite!” is the claim, without further evidence, only a wink and a nod as if to say the claimant has some special inside information and insight into the Magician of Riga, or belongs to an exclusive club of those who do. I’ve done it myself. Hogwash.

All these claims of special insight into the predilections of one of the world’s most popular champions arise from a single slide in Arlindo’s 2012 video, which his blog does not elaborate:

Arlindo’s slide doesn’t even SAY it was “Tal’s favorite.” We all leapt to that specious conclusion ourselves. I’d now characterize Arlindo’s statement as an excited utterance, expressing joy that the pieces could be connected to the charismatic Tal. But it’s not credible evidence that the set was “Tal’s favorite.” All us cognoscenti who imply we have have inside information about Tal’s preferred set, we need to present our evidence, or we need to stop repeating a baseless claim.