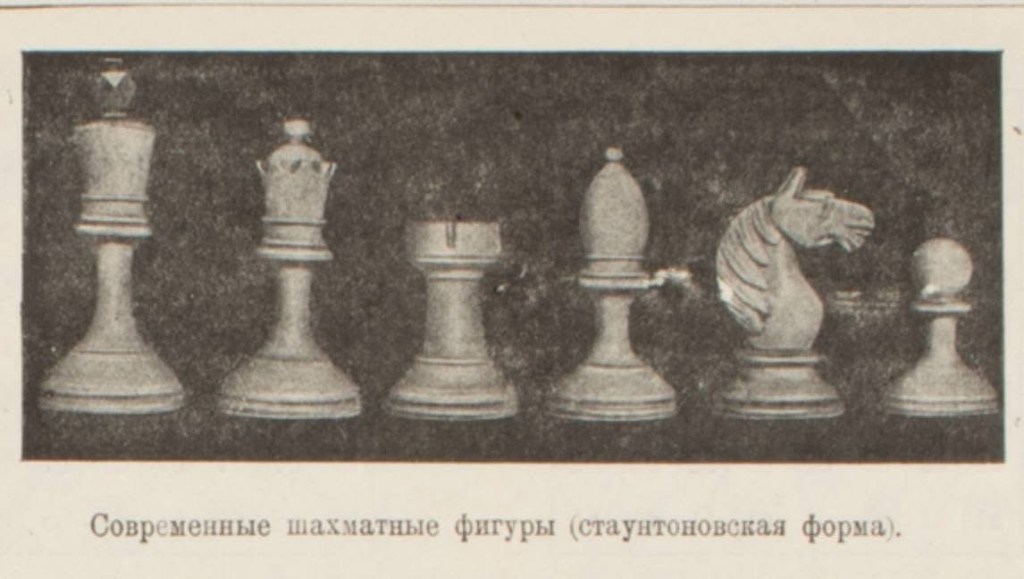

Soviet Master Ilyan Maizelis included a photo of the pictured set in his famous primer “Chess Beginnings” (1937). There he described it as “Modern Chess Figures (Staunton form).” At 9. So the set dates no later than 1937. For sake of convenience, I’ll refer to it as “Maizelis’s Set,” though I have no other evidence that he actually owned or played with one like it.

I recently added such a set to my Soviet and Tsarist collection.

The set is magnificently turned, carved finished, and weighted, with several small defects, a couple chipped coronet tips, broken finials on a White Bishop, a partially broken off finial on the White King, a few cracks and worn finish for character.

The Black King measures 97 mm with its fully intact finial. The Kings’s finials are carved in a unique diamond pattern. The Black pieces are painted with age-consistent wear and chipping, but the White pieces have a finish approximating French polish akin to two Tsarist sets that have matriculated through my collection. Beautiful patina.

The Knight carving is spectacular, the best of any of my Soviet sets and even better than my best Tsarist ones. Highly detailed mane carvings on both sides of the torso. Crisp mouth and eye details. Just spectacular.

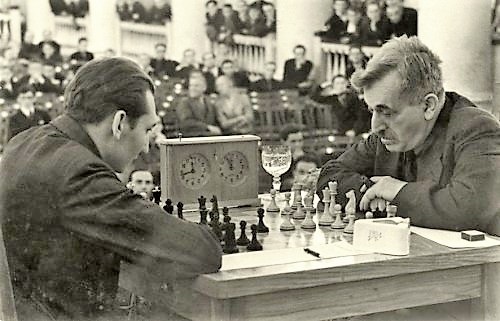

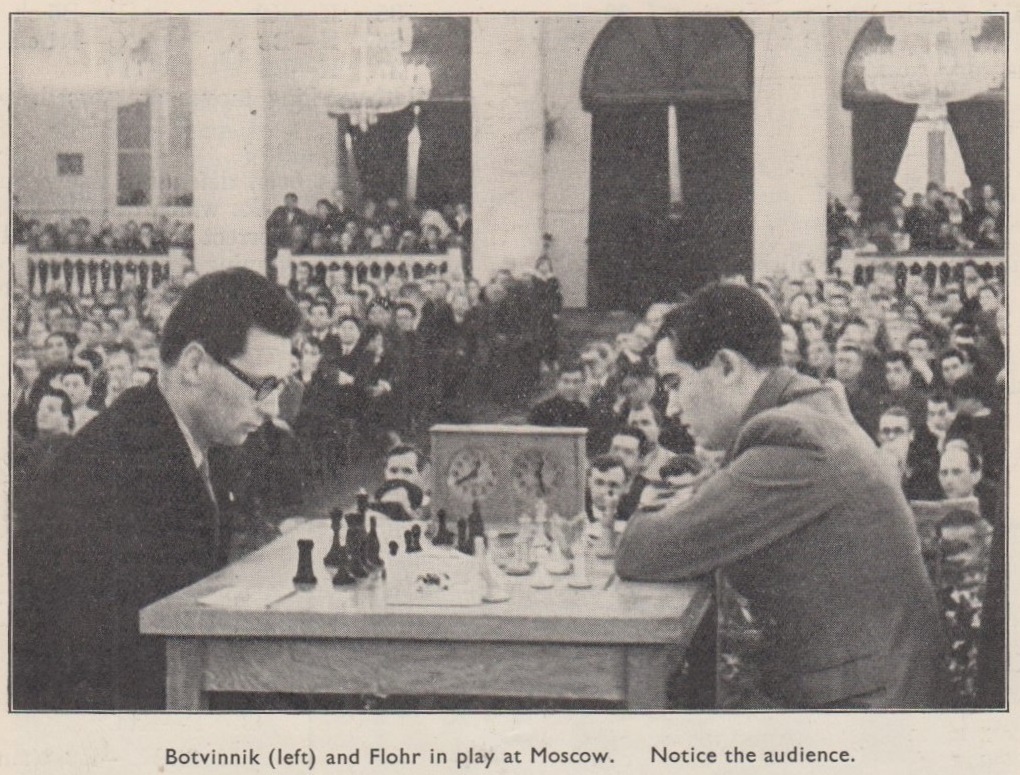

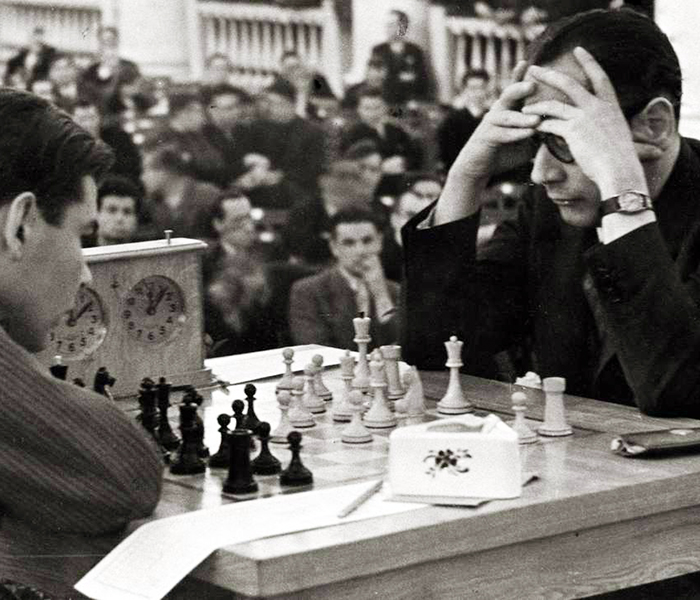

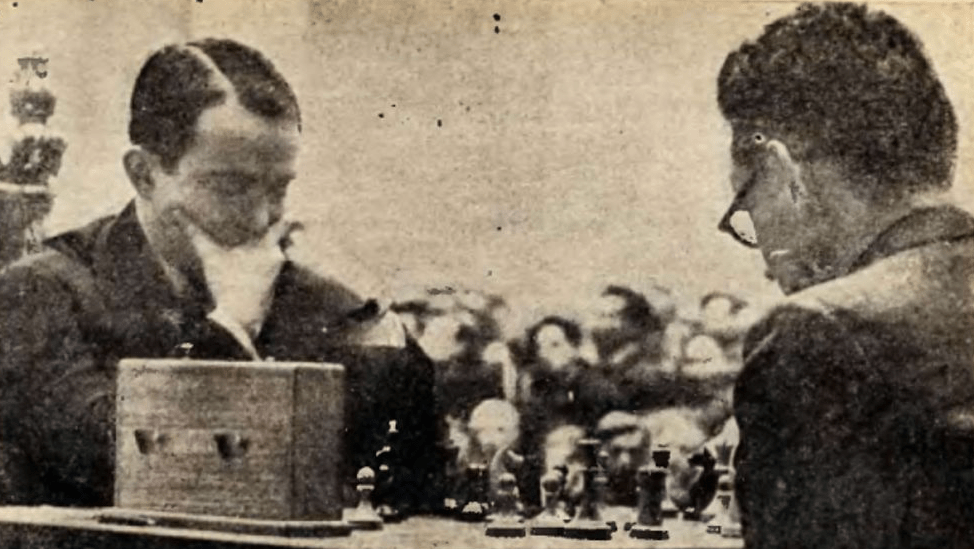

The style is of the group of sets commonly but not unreasonably mistaken for the 1933 Botvinnik Flohr match. I included pictures of several of these sets in my article on the 1933 set.

Shane Chateauneuf recently acquired a beautiful, related set.

The board accompanying my set is wonderful in its own right. Beautiful veneer worn consistent with its age. Gorgeous patina. 53 mm squares are perfectly sized for the pieces, very un-Soviet. None of the asphyxiation that Arlindo Vieira repeatedly complained of. This is perhaps another factor hinting that the set may be much older than 1937.

Simply a gem.

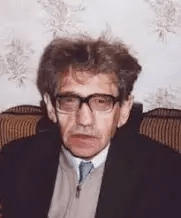

Ilyan Lvovich Maizelis

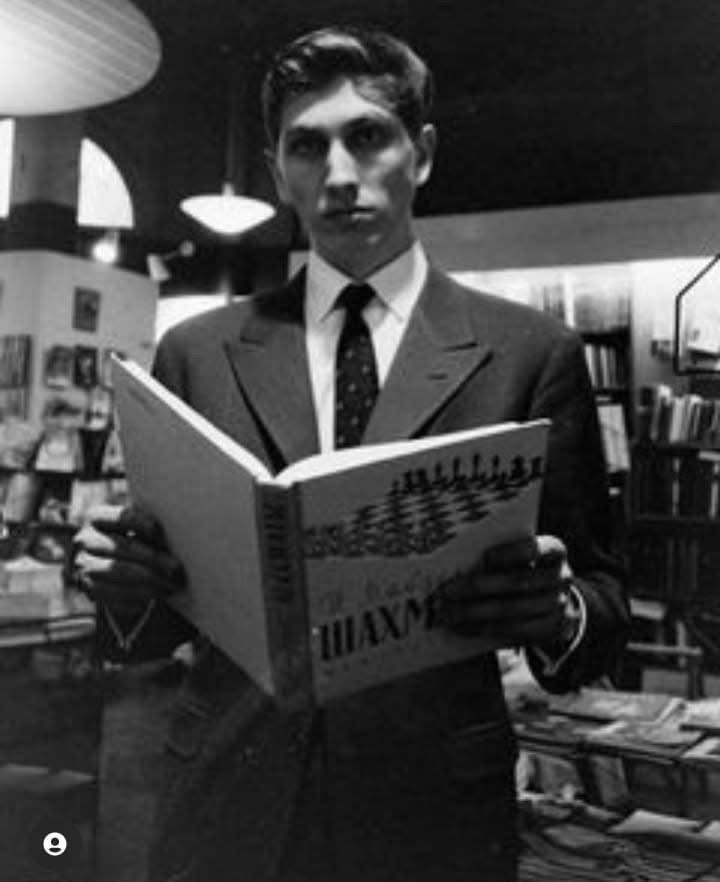

A close friend of Yuri Averbakh, Maizelis was a noted teacher and author, even outside the Soviet Union. No less than Bobby Fischer studied his work.

Soviet chess historian Jorge Njegovic Drndak has compiled this brief biography:

Ilya Lvovich Maizelis (1894-1978)

He was born on December 28, 1894 in Uman, a small village in the Cherkasy region. Having passed college in Ukraine, Ilya won the Union-wide Tournament of Cities in 1924 (a parallel tournament). Once in Moscow, Maizelis quickly joined the chess movement and became one of its most prominent figures.

Having started working as a chess journalist, Maizelis covered the Alekhine-Teichmann match (Berlin, 1921), at that time Alexander Alexandrovich’s name was not yet animated in his homeland. Ended with a score of 3:3.

Ilya Maizelis was close friends with Emanuel Lasker. It was he who during the Moscow International Tournament (1925) handed the great thinker a telegram saying that the work of the second world champion would be staged. The played Lasker ended up getting the foot of the “mill” in the match against Torre, but consoled the young man, who at first considered himself responsible for this defeat of the great chess player.

Maizelis was one of those who convinced Emanuel to move to the USSR, take Soviet citizenship and train for the national team. Shortly before leaving for America, Lasker handed the journalist the manuscript of his children’s book. Ilya’s friend Alexander Ilyin-Zhenevsky believed it was Maizelis’ duty to publish the book, but the work “How Victor Became a Chess Master” was only published in the 1970s.

Ilya Maizelis is a member of the editorial board of the magazine “64”. “Checkers and Chess in a Workers’ Club” (1925-1930), executive secretary of the publication “Soviet Chess Chronicle” (1943-1946), published in English in Moscow under the auspices of the Union Society for Cultural Relations (VOKS). He trained at the Pioneers House of the capital, but at the same time, until the late 1930s, he did not stop the practical performances, performed regularly at the finals of the Moscow championships. In 1932, Ilya Lvovich took fourth place in the championship of the capital and, of course, played in the strength of the master, but did not officially fulfill the title, opting for journalism.

Author of the books “Beginner Chess Player”, “Chess Yearbook 1937-1938”, “Fundamentals of Opening Strategy”, “For 4th Chess Players”. a and 3. “under category”, “Selected games of Soviet and International Tournaments of 1946”, “Chess Textbook Games”, “Tower vs Pawns”, “On the Theory of Tower End”, “Chess Finals. Pawns, Bishops, Horses” edited by Y. Averbakh, “chess. Fundamentals of Theory. Ilya Maizelis translated from German the books “Endgame Theory and Practice” by Johann Berger and “My System” by Aron Nimzowitsch.

With his article, he was the first in the USSR to draw attention to the 1603 painting “Ben Johnson and William Shakespeare,” attributed to Karel van Mander and depicts 17th-century English playwright playing chess. Ilya Lvovich studied the works of the poets Henry Longfellow and Heinrich Hein, translated their works into English and German.

Ilya Maizelis has compiled a chess library that is widely known not only in Moscow and the USSR, but also abroad.

“Everyone knows that Maizelis had the best chess library in Moscow and was often asked to clear up something from an old magazine or a rare book. There was a phone in the room and Ilya Lvovich used to dictate chess and variation games for a long time. Maizelis’ mother-in-law was always in the room, paralyzed and completely indifferent to everything that was going on. He sat like an idol and stared at one point.. And Maizelis, dictating movements, did not say “a-be”, like everyone else, but in a low voice – “a-be”. And then, one day, the mother-in-law, who was apparently tired of this hug to hell, said sadly, “Abe, abe… Fucking idiots! ” (J. Neishstadt).

Shortly before his death, Ilya Lvovich sold the library to good hands to preserve it for posterity. The master of Russian chess journalism passed away on December 23, 1978 in Moscow.