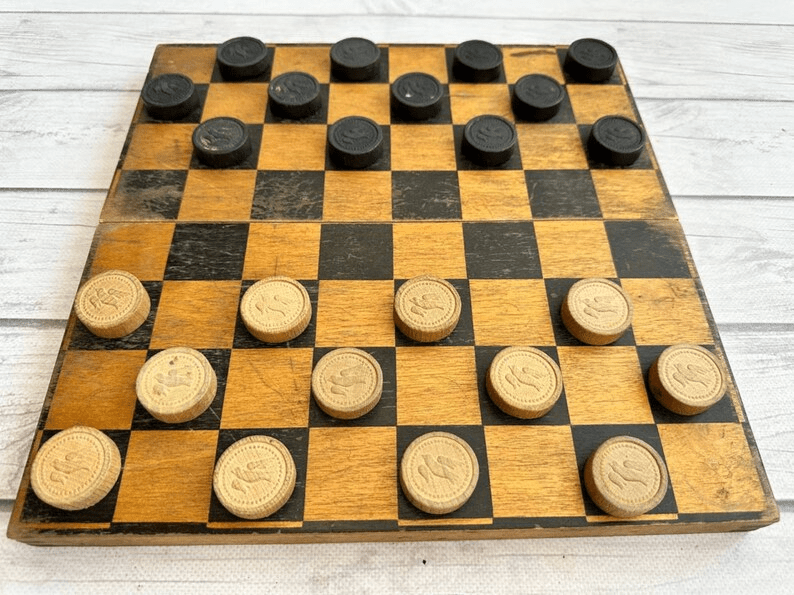

Despite their popularity and longevity, I have hesitated to write about the ubiquitous Valdai Nobles chessmen. It’s not that I don’t like them–I have four specimens in my collection, each with unique attributes. I am fascinated by their design and evolution, particularly the faceted knights characteristic of the mature versions. Nothing has stopped my friends Alan Power and Eva Silvertant from authoring informative articles about them.

Gulag Knights

The reason I have been unwilling to pull the trigger is simple. In his engaging 2019 essay The ‘Gulag’ Knights, Alan claims the Valdai Nobles sets were born in a Gulag in Valdai. Writes Alan:

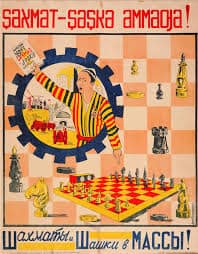

Needless to say, the hundreds of thousands of prisoners snatched up by the Gulag could produce hundreds of thousands of chess sets, and that’s exactly what Stalin had them do. There were two main factories (or camps) that concern this brief discussion. The first “Village” (a polite Stalinist term for a penal colony) was located halfway between the main artery connecting St. Petersburg and Moscow, namely, The Valdai Regional Industrial Manufactory in Novgorod (450 km north-west of Moscow), a picturesque and densely forested area used today by the rich and famous (including Putin and his entourage) for quick summer getaways. The second ‘village’ is the Yavas Township located in the Central Volga Region of Mordovia (500km south-east of Moscow)… From these two camps came the so-called ‘Valdayski’ and Mordovian (f.k.a. “the Latvian”) sets respectively…

These are intriguing claims. As a skeptic and empiricist, I began to explore their basis. Insofar as they relate to Mordovia, they are very well-supported. But as for Valdai, Novgorod Oblast, halfway between Leningrad and Moscow, I could find no evidence of a Gulag.

From a temporal point of view, it is plausible that Nobles sets of the 1940s and 1950s were made in a Gulag. But upon Stalin’s death in 1953, the general amnesty that granted Gulag prisoners with sentences of five years or less drastically cut back the Gulag system, and in 1960, Khrushchev abolished its remnants. Thus, even if the sets of the fifties and sixties could have been manufactured in a Gulag, those of the sixties could not have been. Beyond this, I simply could neither corroborate nor refute Alan’s claim.

Still, I kept searching Gulag databases and secondary sources without finding a link between Valdai and the Gulags. As I often do, I discussed the issue with my friend Sergey Kovalenko of St. Petersburg. Sergey is a well-respected chess collector, skilled carver, and denizen of Russian and Soviet archives. He regularly discusses historical issues and shares archival research with me and others. Like me, Sergey was intrigued by Alan’s claim. Like me, he could neither confirm nor refute it.

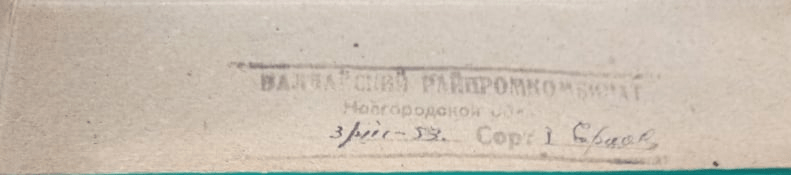

Sergey agreed with Alan’s claim that the Nobles sets were manufactured by the Valdai Regional Industrial Manufactory in Novgorod. This was evidenced by cardboard boxes like Alan’s bearing the producer’s name, Валдайский Райпромкомбинат, or Valdai Raipromkompromat, meaning Valdai Regional Industrial Plant. Unlike Alan, however, I do not equate the term Village with Gulag, and am unaware of any etymological or historical reason for doing so.

Nearest Gulag Camp Dug Missile Silos

Perhaps the most comprehensive online Gulag databases are maintained by Gulagmap.ru and Gulag.cz. These sites compile data on individual camps, with detailed information about each taken from the primary Russian language source, Система исправительно-трудовых лагерей в СССР (System of Forced Labour Camps in the USSR [M. B. Smirnov, comp. 1998]) and other archival material. These online databases provide interactive maps of Gulag camp administrations as interfaces. Neither lists any camp in Valdai, Novgorod Oblast.

Nor does the print version of Smirnov’s encyclopedia of Gulag camps. The camp nearest to Valdai was named EM ITL. It was located about 22 kilometers from Valdai near Dubrovets and engaged primarily in the construction of missile silos. Sergey provided the following map illustrating the location of ITL EM in relation to Valdai (Валдай), Novgorod Oblast.

According to gulagmap.ru:

ITL “EM” was formed on January 10, 1951 and operated until May 14, 1953, when it was reorganized into the Dubogorskoye LO. The camp administration was located in the area of the Dvorets station of the Kalinin railway. In operational command, it was initially subordinated to the Main Directorate of Industrial Construction Camps, but shortly before the camp’s reorganization, it came under the jurisdiction of the GULAG of the Ministry of Justice. The maximum number of prisoners held here was recorded in 1953 and amounted to 2,062 people.

ITL “EM” was engaged in the construction of defense facilities. In April 1952, the construction was assigned the first category of secrecy, and prisoners could be sent to this camp only with the permission of the Ministry of State Security…

According to sources, prisoners of the ITL “EM” were engaged in the construction of a coal mine and the maintenance of Construction 714, as well as the excavation of shafts and tunnels. In reality, the camp’s task was the construction of missile silos. The labor of prisoners of the ITL “EM” was also used to build locomotive and diesel power plants.

Likewise, Avraham Shifrin’s The First Guidebook to Prisons and Concentration Camps of the Soviet Union (1982) makes no mention of a Gulag camp in Valdai. At 276-277, 389. Nor does Anne Applebaum’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Gulag: A History (2003). At 676.

Post-Gulag Prison Colony ITK-4

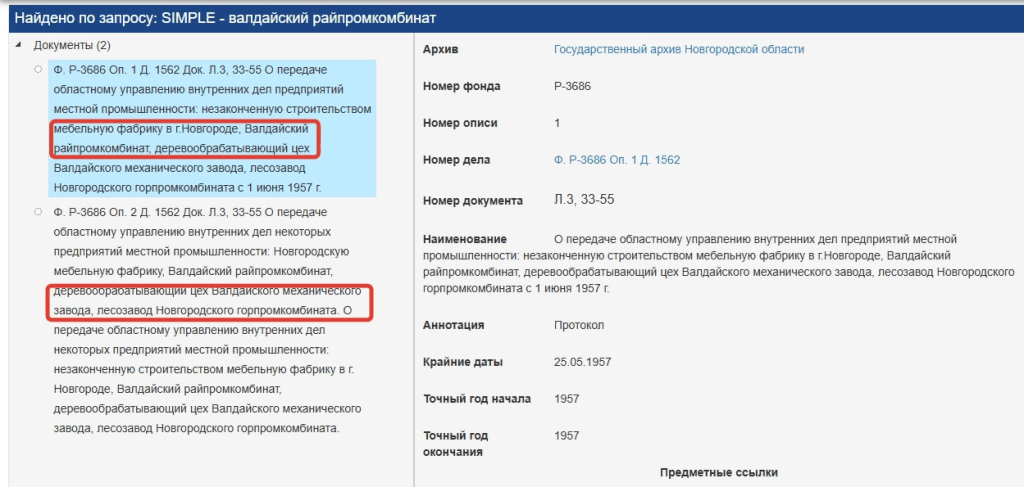

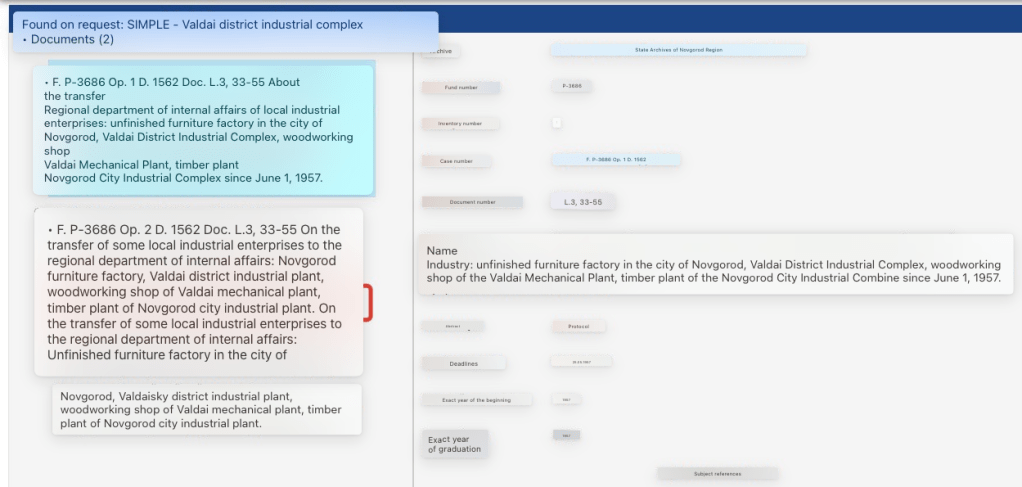

Sergey accessed the Novgorod Online Archives and made an intriguing discovery. He discovered a link between the Valdai Industrial Plant and the post-Gulag Soviet correctional system, if not with the Gulag system itself. According to the Novgorod Archives, on 1 June 1957, various assets in and around Valdai were transferred to the Department of Internal Affairs (MVD), among them the Valdai District Industrial Plant, the woodworking shop of the Valdai Mechanical Plant, and the Timber Plant of the Novgorod City Industrial Plant.

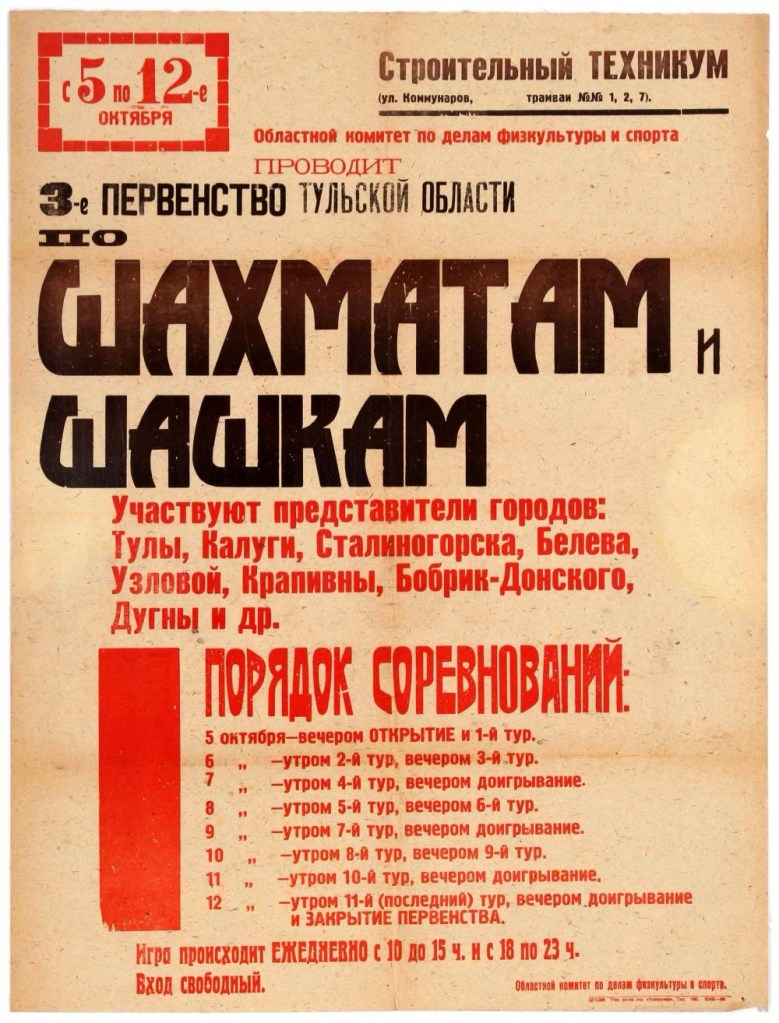

According to records Sergey found, the woodworking shops and other assets were transferred to a newly organized correctional and labor colony in Valdai, Novgorod Oblast, designated ITK-4, or Labor Colony 4, and OYA-22/4. The MVD received funds to construct housing and other structures in Valdai and the nearby town of Myza to accommodate 700-800 male prisoners. V. M. Skoryukov was appointed Deputy Chief of ITK-4 for Production. When prisoners began arriving in October of 1957, they worked in two lathe, furniture and plywood workshops, and a forest in a nearby village.

It is essential to situate ITK-4 in the history of the Gulag system. According to a recently declassified 1951 CIA report, two kinds of labor facilities operated within the Gulag system. ITLs–Labor Camps–were established in remote regions and housed prisoners with sentences of two years or greater. By contrast, ITKs–Labor Colonies–typically housed petty criminals in each oblast.

Even before Stalin’s death, MVD Minister Laventry Beria and his deputy Stepan Mamulov proposed to drastically cut back and replace the Gulag system. Stalin died in March 1953. While his corpse was still warm, Beria began to dismantle the Gulags, issuing a general amnesty that led to the release of 1.5 million prisoners–60% of the Gulag population–over the next three months. Aleksei Tikhonov, The End of the Gulag, in The Economics of Forced Labor: The Gulag (P. Gregory and V. Lazarev eds., 2003) at 67-73. Anne Applebaum writes:

As Khrushchev had feared, Beria, who was barely able to contain his glee at the sight of Stalin’s corpse, did indeed take power, and began making changes with astonishing speed. On March 6, before Stalin had even been buried, Beria announced a reorganization of the secret police. He instructed its boss to hand over responsibility for the Gulag to the Ministry of Justice, keeping only the special camps for politicals within the jurisdiction of the MVD. He transferred many of the Gulag’s enterprises over to other ministries, whether forestry, mining, or manufacturing. On March 12, Beria also aborted more than twenty of the Gulag’s flagship projects, on the grounds that they did not “meet the needs of the national economy.” Work on the Great Turkmen Canal ground to a halt, as did work on the Volga–Ural Canal, the Volga–Baltic Canal, the dam on the lower Don, the port at Donetsk, and the tunnel to Sakhalin. The Road of Death, the Salekhard–Igarka Railway, was abandoned too, never to be finished.

Supra, at 478.

In 1955, the GUITK (Glavnoye Upravleniye Ispravitelno-Trudovykh Kolony), or Chief Administration of Corrective Labor Colonies, was established within the MVD to administer the post-Gulag correctional system. After Khrushchev gave his famous speech denouncing Stalin in February 1956, the dismantling of the Gulags accelerated. Appleman writes:

In the months that followed the secret speech, the MVD also prepared to make much deeper changes to the structure of the camps themselves. In April, the new Interior Minister, N. P. Dudorov, sent a proposal for the reorganization of the camps to the Central Committee. The situation in the camps and colonies, he wrote, “has been abysmal for many years now.” They should be closed, he argued, and instead the most dangerous criminals should be sent to special, isolated prisons, in distant regions of the country, specifically naming the building site of the unfinished Salekhard–Igarka Railway as one such possibility. Minor criminals, on the other hand, should remain in their native regions, serving out their sentences in prison “colonies,” doing light industrial labor and working on collective farms. None should be required to work as lumberjacks, miners, or builders, or indeed to carry out any other type of unskilled, hard labor.

Dudorov’s choice of language was more important than his specific suggestions. He was not merely proposing the creation of a smaller camp system; he was proposing to create a qualitatively different one, to return to a “normal” prison system, or at least to a prison system which would be recognizable as such in other European countries. The new prison colonies would stop pretending to be financially self-sufficient. Prisoners would work in order to learn useful skills, not in order to enrich the state. The aim of prisoners’ work would be rehabilitation, not profit.

Supra, at 509.

By 1957, GUITK became primarily responsible for operating and administering that system. It was within the post-Gulag framework Dudorov described that Valdai’s ITK-4 went operational.

Another Valdai and Segezhlag

Sergey did find some connection between a Valdai and the Gulags, but it was a different Valdai, one located in the Segezha District of Karelia, almost 900 km north of its namesake in Novgorod Oblast. This Valdai lies within the same Segezha District as a Gulag camp known as Сегежский ITL, or Segezhlag, but across from it on Lake Vygozero and 132 km distant by road. This Valdai was founded in the early 1930s to aid in constructing the White Sea-Baltic Canal with Gulag labor.

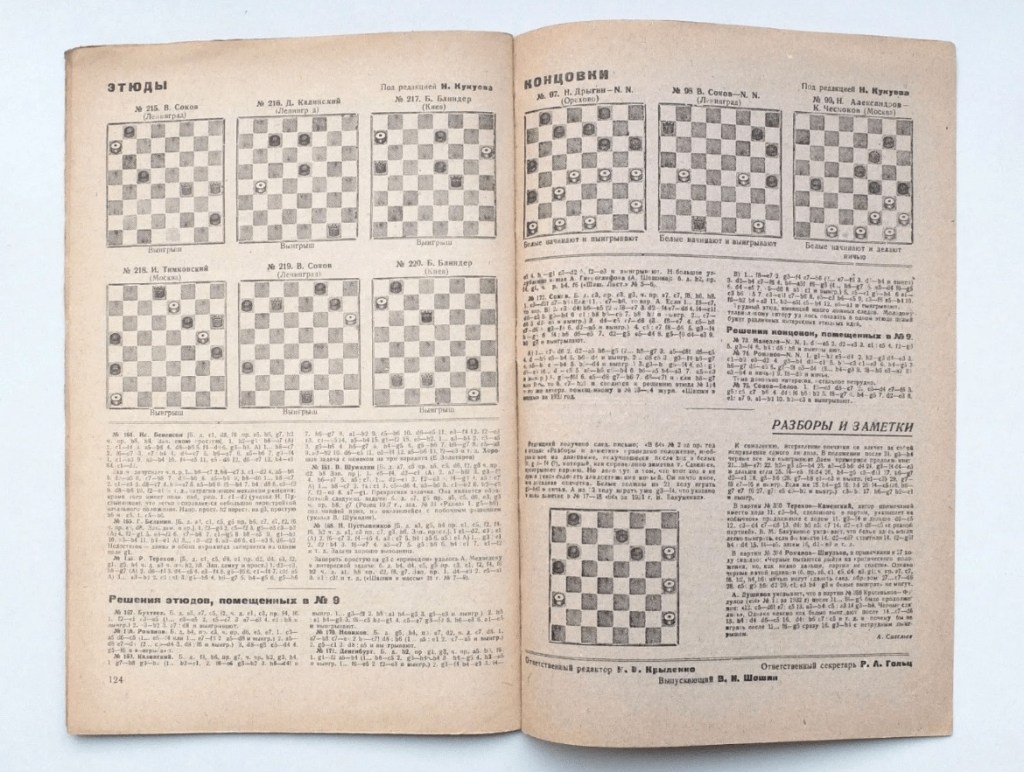

Segezhlag was organized in 1939. According to gulagmap.ru:

The Segezha Corrective Labor Camp was organized no later than October 21, 1939, on the basis of the 4th camp division of the White Sea-Baltic Corrective Labor Camp and operated until June 28, 1941. The camp administration was located in the Karelo-Finnish SSR, in the area of the Segezha station of the Kirov Railway. Initially, the camp was subordinate to the GULAG, but from February 1941 it came under the jurisdiction of the Main Directorate of Industrial Construction Camps (GULPS). Up to 7,951 prisoners were held here…

The labor of the prisoners of the Segezha camp was used for the construction of the Segezha timber and paper plant, the Segezha hydrolysis plant (since November 1940), the Kondopoga sulfite-alcohol plant (since March 1941), for servicing the first stage of the timber and paper plant, as well as sawmills, foam concrete, concrete, asphalt plants, a concrete products plant, for the construction of railways and dirt roads, residential and utility facilities, and agricultural work.

See also Smirnov, supra, at 390.

There is no record of chess set production at Segezhlag. While the Gulag camp there closed in 1941, Penal Colony No. 7 continues to operate there.

Conclusion

The Nobles chess sets of Valdai were not made in a Gulag, but in the woodworking shops of the Valdai District Industrial Plant. Prisoners of the Gulag camp nearest the chess-producing Valdai dug missile silos, but did not turn chess pieces or carve knights. Ironically, a different Valdai was associated with a Gulag camp, Segezhlag. But this camp had nothing to do with the production of chess sets either.

After 1957, however, sets were made by forced labor within ITK-4 of the Soviet prison system, confirming a key component of Alan’s initial claim concerning these sets. Still, the change in penal regimes was not a distinction without a difference, a mere “changing of the uniforms,” to borrow a phrase from Budapest’s House of Terror Museum. If we were to equate the two different penal regimes, we would unfairly diminish one of the most immediate and significant consequences of Stalin’s death–the abolition of the Gulag system, the release and rehabilitation of millions who had unjustly suffered under its iron hand, the reconfiguration of penal institutions, and all the social dislocation that attended the Gulag’s demise.

Many thanks to Sergey Kovalenko and the reference librarians at the Bedford, NH Public Library.