Andrei Nikolaevich Hardin (1842-1910) was a Russian lawyer and chess player. He was born and lived in Samara.

According to Alexandr Yanushvesky:

Andrei Nikolaevich Hardin was passionately fond of chess. He subscribed to a great deal of foreign chess literature and could sit alone at the board for hours. According to him, he learned to play well because, having found himself somewhere in the wilderness and having a lot of free time, he would sit for days reading chess literature and studying the theory of this game. For about a year or a little more, he did not play with anyone, and after this sitting, having met Chigorin, he showed himself to be a first-class player.

“Andrey Nikolaevich Hardin is the very first Samara extra chess player,” Learning and Playing Chess (26 September 2022), https://vk.com/@-198251430-hardin-andrei-nikolaevich-samyi-pervyi-samarskii-ekstra-sh

Hardin came to play correspondence chess with one Vladimir Ilych Lenin, who became Hardin’s law clerk when Lenin moved to Samara. They continued playing chess, with Samara giving Lenin various odds.

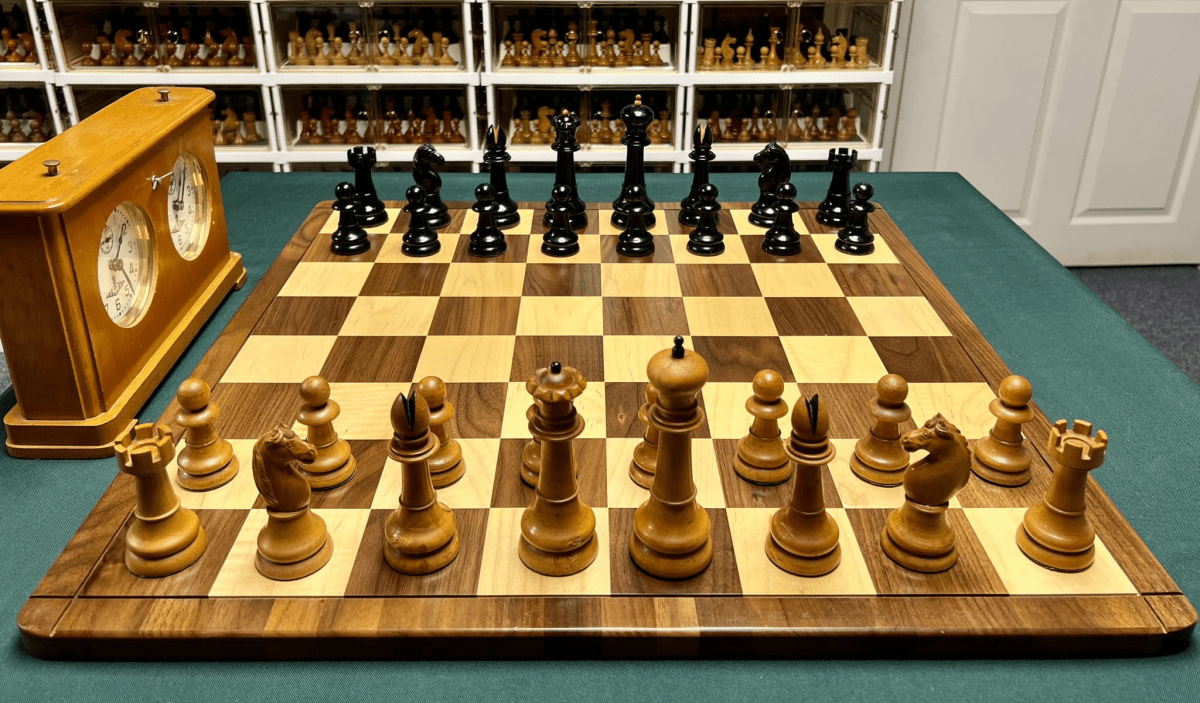

Two photos of Hardin taken with a chess set are known.

https://vk.com/@-198251430-hardin-andrei-nikolaevich-samyi-pervyi-samarskii-ekstra-sh

While Hardin’s garb suggests that these photos were taken at different times, they most certainly appear to feature the same set and the same location. Perhaps it was Hardin’s apartment in Samara, where he played Lenin. Indeed, it well may have been the very set that he and Lenin played with.

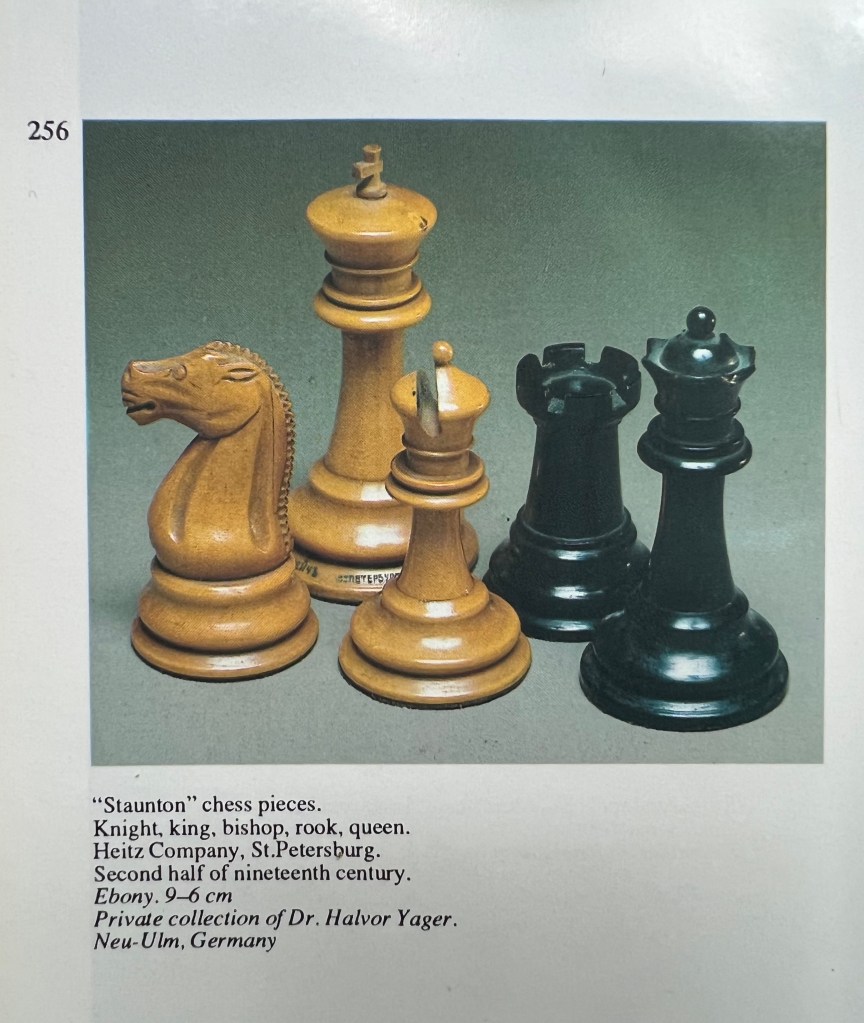

Hardin’s set is a smaller version of what we have come to know as the “Alekhine Set,” a moniker attached to it by Singapore collector Steven Kong, who acquired it from a dealer in St. Petersburg, Russia. The set now resides in my collection.

The set is tall and heavy, finely turned, carved, and finished . The pieces have a large height to base width ratio, but their weight keeps them stable in play. The king is five inches tall with a bulging crown characteristic of Tsarist sets and reminiscent of Austrian onion top sets. The queen’s coronet eschews sharp points, protecting it from damage during the rigors of play. The bishop’s miter is unique, the cut splitting it into two equal halves. The knight’s mane flows with detail, and its features are carefully carved. The rook’s turret is exaggerated, its merlons tall and distinctly cut.

A magnificent set. A jewel. Of the finest craftsmanship a Tsarist workshop could be expected to provide.