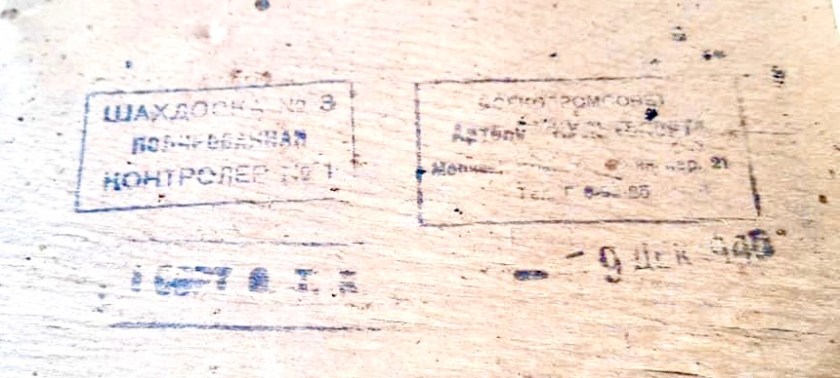

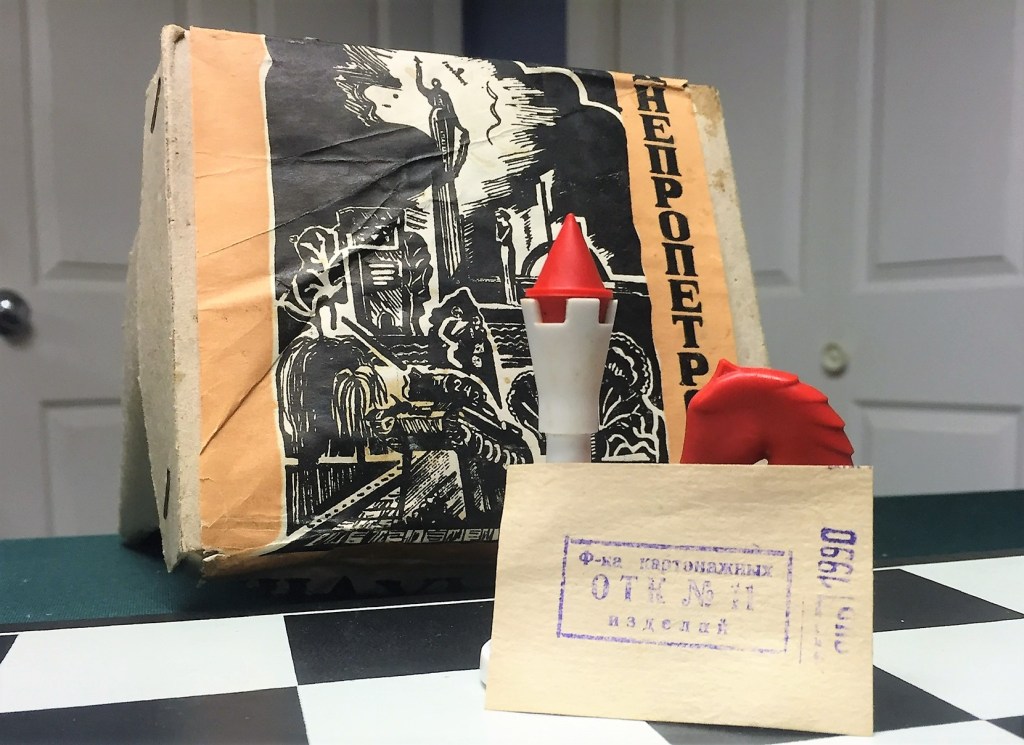

Studying Soviet chess sets forces us to confront a good number of uncertainties. In many cases, direct evidence of a set’s provenance is simply lacking. Secondary information is scarce, even more so information that is available in English. So it is with these beautiful pieces and the board with which they came to me, which bears stamps that read: Leningrad Factory No. 8, 1943. Here is a close-up of the board’s stamps.

The Pieces

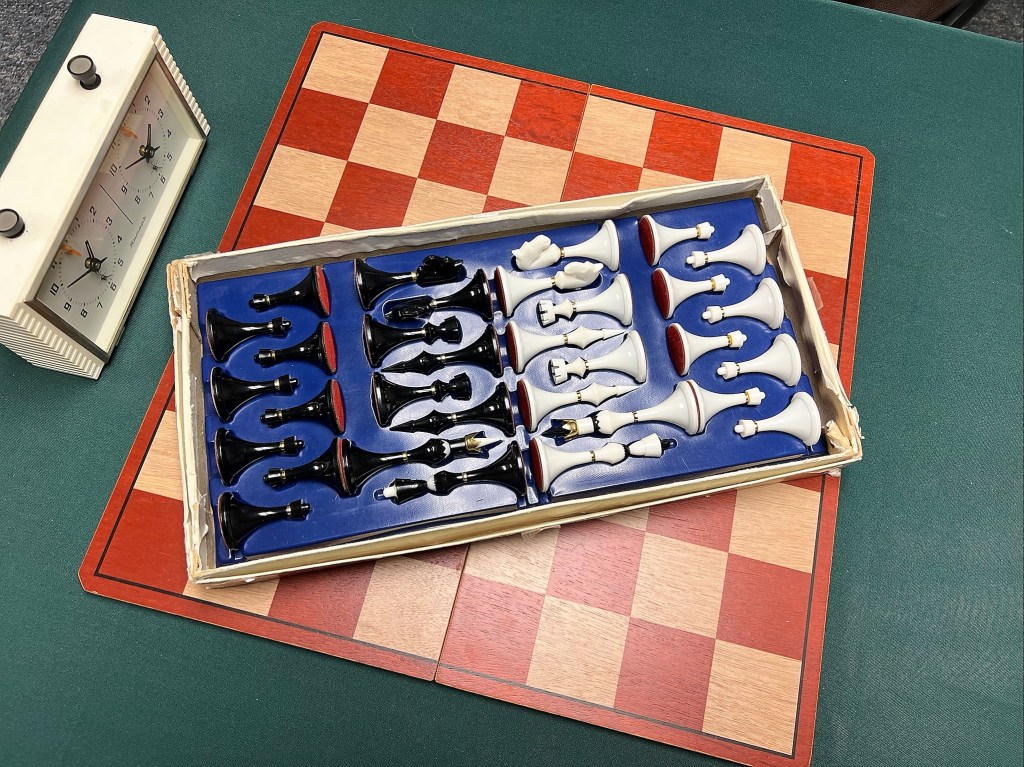

Here are the nicely turned and carved red and black pieces arrayed on the board.

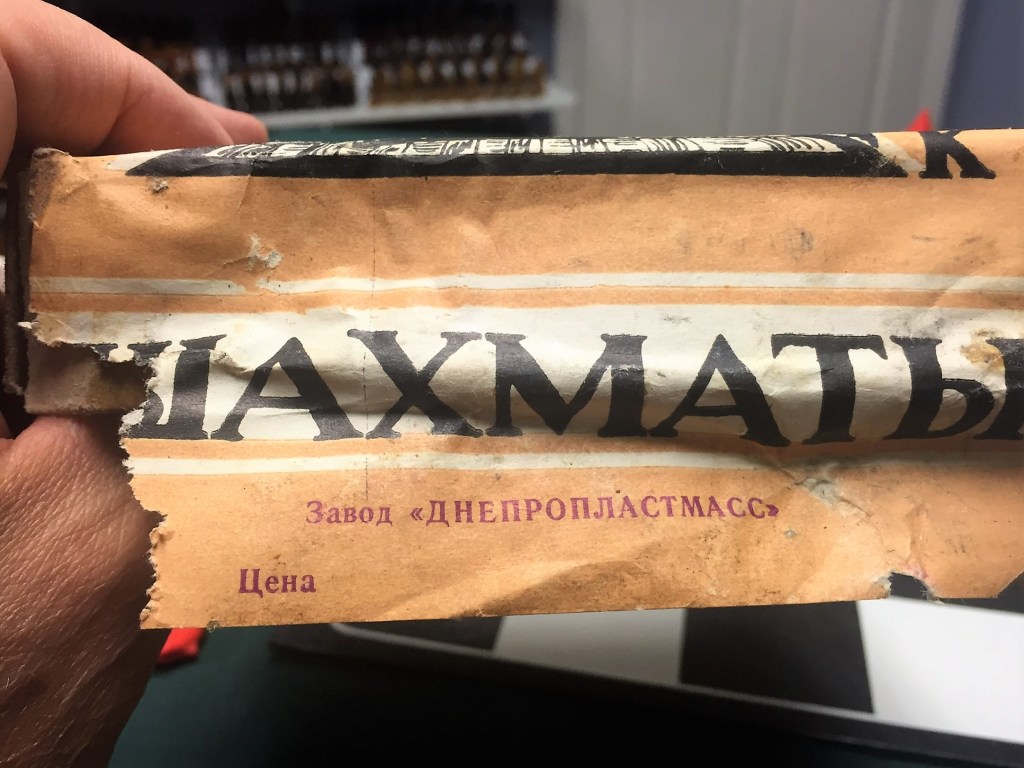

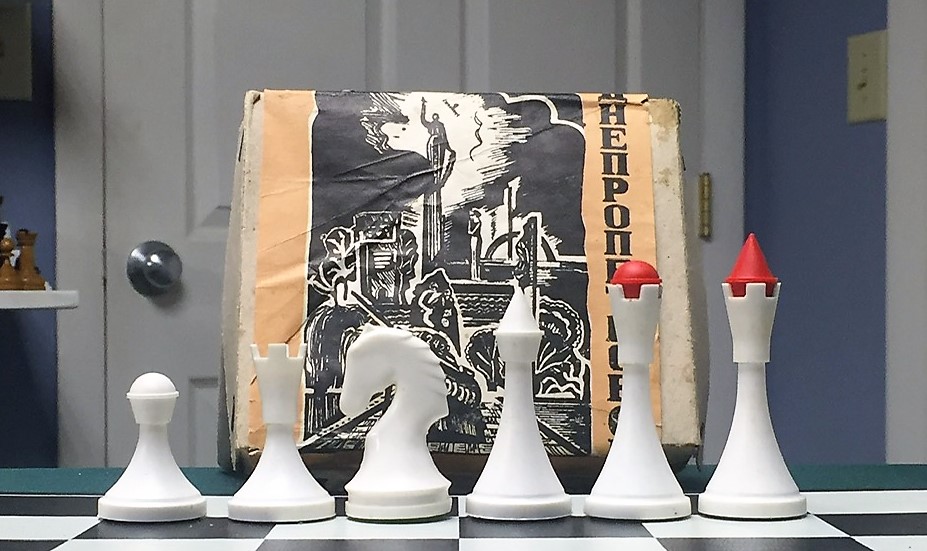

I initially thought that the stamps signified that the pieces and board both originated in Nazi-besieged Leningrad, writing, “It is nothing short of miraculous that the set survived, as wood shortages doomed most wooden sets to the stoves to survive the brutal winters.” But evidence soon emerged that the board was paired with the pieces sometime after they were manufactured. Here are two photos that seem to show these same pieces being offered for sale in a different container.

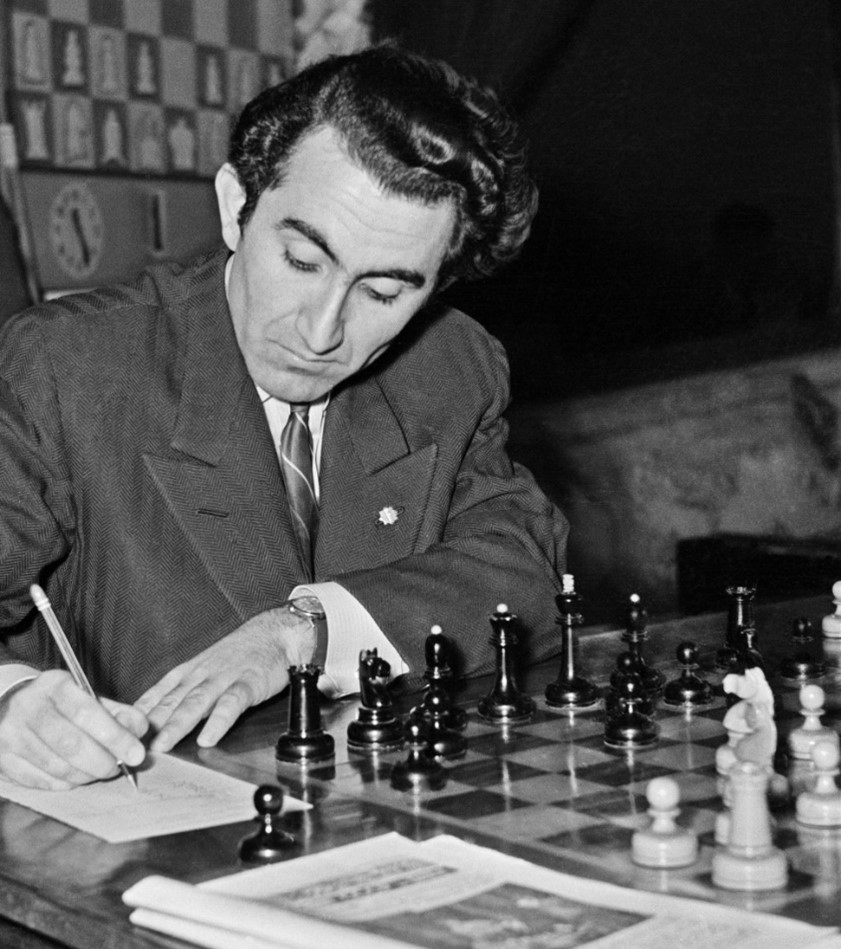

The dropped jaw of the knights, the steeple rings of the bishops, and style of the stem and base suggest this is what we typically call a “Laughing Knight” set. At the same time, the pieces also incorporate a slender verticality and stem and base structure reminiscent of the Soviet Upright chessmen sometimes called “Averbakh II” pieces, mistakenly implying a stylistic relation to the set Averbakh is seen playing with in a well-known photo from the 1949 Moscow Championship.

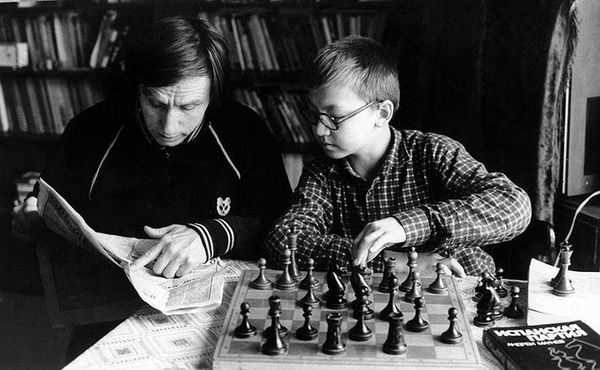

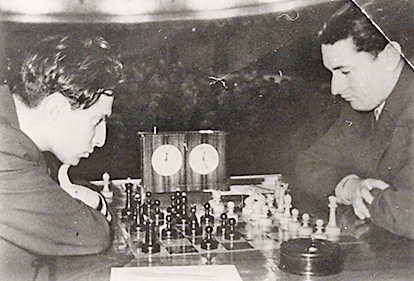

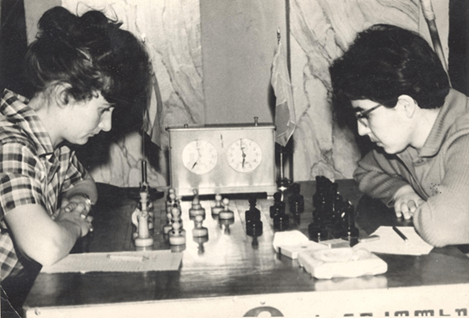

All this said, the set is unweighted, which is a noted characteristic of sets manufactured while the Soviet Union was on a war footing, metal being needed for weapons and munitions production. And there is photographic evidence circumstantially linking sets like this one to Leningrad. Here is a photo of a like set being played with by then-future World Champion Lyudmila Rudenko (b. 1904).

Although this photo is undated, Rudenko’s first major success in chess was her victory in the 1928 Moscow Championship, and it is said that her style and form did not finally develop until she moved to Leningrad in 1929 and began studying under the likes of Romanovsky and Tolush. It is conceivable that she is twenty-five in the above photo.

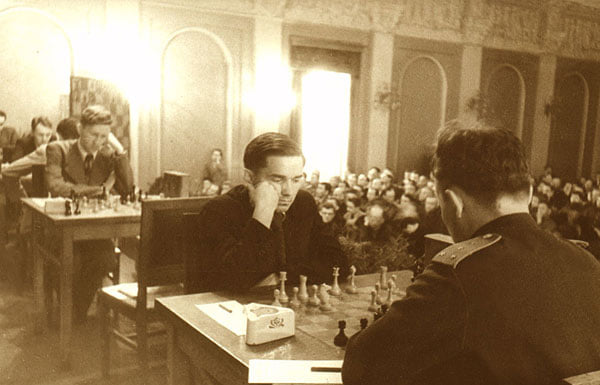

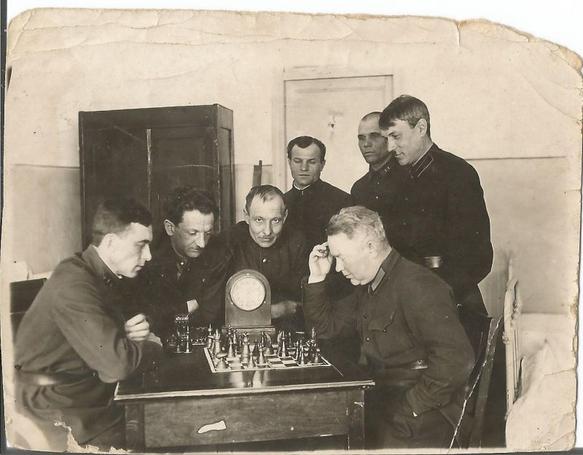

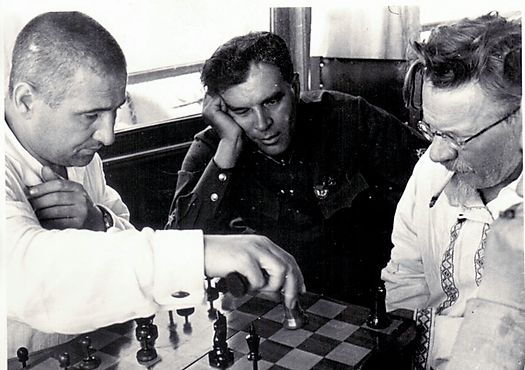

Rudenko is not the only public figure circumstantially linking the set to Leningrad. Below is a photo of Mikhail Kalinin, who was born in 1875, moved to St. Petersburg 1n 1895, undertook revolutionary activity in 1905, and became one of the earliest members of the Bolshevik Party. In 1917 he became mayor of Petrograd, and in 1919 a member of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party. He ascended to full membership in the Politburo in 1926. Kalinin served as titular head of the Soviet state from 1917 until his retirement in 1946, a largely ceremonial role. Of him Khrushchev supposedly said, “I don’t know what practical work Kalinin carried out under Lenin. But under Stalin he was the nominal signatory of all decrees, while in reality he rarely took part in government business. Sometimes he was made a member of a commission, but people didn’t take his opinion into account very much. It was embarrassing for us to see this; one simply felt sorry for Mikhail Ivanovich.” One could not feel too sorry for him. It was very rare for any Bolshevik of consequence to have survived the Great Purges of the 1930s, and his signature could be found authorizing heinous acts like the murder of thousands of Polish prisoners, signed ceremoniously or not. If Kalinin is sixty in the following undated photo, then it was taken around 1935.

Further photographic evidence likely links pieces like these to the mid- to late-1930s. St. Petersburg collector and researcher Sergey Kovalenko dates the following photo to be from 1935.

The set also appeared in other finishes. Here is a dark red/brown and black specimen from Steven Kong’s collection. It originally was finished in a black and orange/red combination. It is unweighted.

And here is a magnificent specimen from Steve’s collection, in a natural finish. These pieces are weighted, perhaps signifying they are an early version of the design. The exquisite dental work seen in the knight on g1 supports an early dating.

The Board

We have seen the stamps inside the board above. The board itself is constructed from plywood. It is roughly 40 cm square. Its squares are irregular, ranging from 45-50 mm. The dark squares and sides are finished with a reddish-brown stain. The board seems to have gone through several generations of hooks and hinges. Notation was added to the borders after market.

Sergey Kovalenko assesses the board as follows: “Such simplifications are typical for boards of the 60s, but, in my opinion, this is also normal for wartime. The colors look early. In any case it is interesting board. Some of evacuated Leningrad factory could make this board, for example.”

The Factory

What was Leningrad Factory No. 8, and could it have made chessboards amidst the devastating siege?

According to Russian sources unearthed by Sergey, Leningrad Factory 8 was an electromechanical plant launched in 1934. It produced radio broadcasting equipment, charging stations, welding units, related boxes and coils. In July 1941, it merged with the Molotov Telephone plant into a single enterprise, and much of the plant’s equipment and personnel were shipped to Molotov, which was renamed Perm in 1957, a large industrial center on the Kama River and near the Ural Mountains. The joint plant in Molotov began operation in September 1941 located on the site of the former confectionary plant Red Ural, and was renumbered as Plant No. 629. In May 1942, a woodworking operation was added to the joint plant. Among its products were wood boxes for military telephones manufactured at the plant.

There is no evidence that either Sergey or I could find of what, if anything, any remnants of Plant No. 8 remaining in Leningrad may have produced. According to Wikipedia, “86 major strategic industries were evacuated from the city. Most industrial capacities, engines and power equipment, instruments and tools, were moved by the workers. Some defense industries, such as the LMZ, the Admiralty Shipyard, and the Kirov Plant, were left in the city, and were still producing armor and ammunition for the defenders.” According to the Museum of the Siege of Leningrad, “upon the outbreak of hostilities, the leading enterprises of Leningrad were reoriented to produce weapons and ammunition. In January 1942, at the most critical time of the blockade, 22 enterprises produced more than 100 types of military equipment, weapons, ammunition, communications equipment, instruments, and so on.”

Based on this information, two possibilities present themselves for the origins of the Leningrad Factory No. 8 board. The first is that it was manufactured in Leningrad by remnants of the plant remaining there after the bulk of its productive assets were evacuated to Molotov. It is conceivable that these remnants continued to manufacture military phones for use by the besieged defenders, and that scraps from the phone boxes were used to fashion some crude chess boards. Communications equipment is among that believed to have been made there during the siege. But there is no direct evidence of woodworking to have continued there, and it seems unlikely that scraps from the production of military phones were used to make luxury goods when thousands were freezing to death for lack of fuel, even under Stalin.

The second possibility is that the stamps from Leningrad Factory No. 8 traveled to Molotov with the bulk of the plant’s other assets, and were used to stamp chessboards made in the merged plant’s woodworking shop from scraps from the production of wooden boxes for military phones, even though the joint plant had been relocated and renumbered. I find this possibility more plausible than the first.

Finally, a third possibility must be considered. That is that the stamp inside my board is not from Factory No. 8, but Factory No. 3. Russian sources tell us that Leningrad Factory No. 3 began making gramophone records in the mid-1930s and children’s toys and radios in the late 1930s, but lacked its own woodworking shop. For this reason, as well as the circumstances of the siege outlined above, I find it unlikely to have been the manufacturer of my chessboard.

Conclusion

This slender, elegant set with wide bases incorporates a design that originated in the 1930s, but it is highly unlikely that it was turned and carved in besieged Leningrad, even though it has several discernable links to that city. The board that housed it when it came to me bears stampings literally telling us it was made by Leningrad Factory 8 during the siege, but there are good reasons not to interpret them literally. More plausibly, the stamps evacuated Leningrad in 1942 with the bulk of the plant’s productive assets, only to be used in Molotov, their new home near the Urals, and were affixed to a board made by the Molotov plant’s woodworking shop from scraps of plywood left in the production of boxes for military telephones. Many thanks to Sergey Kovalenko for sharing his research and thoughts on this curious case.