The history of checkers paralleled that of chess in the Soviet Union. Both games had been played for centuries, despite suffering the disapprobation of the Orthodox Church. Both were incorporated into the Soviet state’s political program to elevate and enrich the cultural level of the masses.

According to the Russian Checkers Federation, “games similar to modern Russian checkers were known to the Eastern Slavs as early as the 4th century, as indicated by numerous artifacts from archaeological excavations. References to checkers (or ‘tavleys,’ as this game was previously called in Rus) are found in some epics and other written evidence from that time.” https://shashki.ru/variations/draughts64/ During the reign of Peter I (1682-1725), checkers became popular. The first article about checkers appeared in 1803. https://www.sports.ru/others/blogs/2699763.html

Official rules were printed in 1884, and the first Russian championship was held a decade later, with the second, third, and fourth All-Russian championships played in 1895, 1898 and 1901 respectively. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_draughts A magazine dedicated to the game began publication in 1897. According to Russian author Maria Selenkova, by checkers had become popular, with skilled players emerging in various neighborhoods, playing in matches and and informal tournaments, and sharing their knowledge with the younger generation. https://www.sports.ru/others/blogs/2699763.html

Like chess, the Russian game is played on a board with eight rows and eight ranks, the former designated by letters a-h and the latter numbers 1-8, the algebraic system familiar to modern chess players. The rules are similar to the game played in the United States, except that all pieces may capture forward or backward. Soviet players competed internationally, playing the 10 x 10 square version of draughts. Competitive games are timed, using chess clocks, and recorded using algebraic notation. Competitive players are rated using an Elo system. https://shashki.ru/federation/

During the early 20th century, checkers attracted a diverse demographic, including soldiers, workers, and traders. The game’s popularity continued to grow following the revolution, as the new government recognized the public’s interest in checkers, viewing it as a more dynamic and simpler alternative to chess.

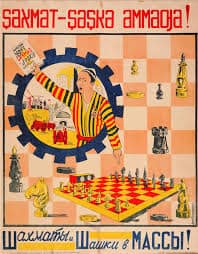

Like chess, checkers was taken very seriously in the USSR was actively promoted by the Soviet state. In August 1924, the All-Union Chess and Checkers Section was established. Bolshevik and state prosecutor Nikolai Krylenko presided over the section. Under the section’s auspices the first USSR checkers championship was played the same year.

Krylenko spoke of the games jointly as the “chess and checkers movement.” He wrote:

Ever since the conception of our organization, we have our slogan, Chess and Checkers into the Working Masses. We came up with this slogan to combat the theory that chess is pure art, the theory that chess is just art for art’s sake. The struggle for masses, the struggle for introduction of chess and checkers to the masses as a weapon of the cultural revolution – this is our first slogan, which we carry out ever since our organization was born.

The comrades who read our political literature, our specialized chess and checkers literature, knew clearly that if we wanted to make our movement, firstly, proletarian, and secondly, truly widespread, then the conclusion should have been obvious: a mass movement, a working-class movement is ought to be a political movement. It’s plainly impossible for the working masses, who every day take active part in the country’s political life, who every day, every hour are involved in their country’s international and internal policy – for those working masses, when they study chess and checkers in clubs, or at home, or wherever, to cease being what they are: being political activists and builders of their own state, arbiters of their country’s destiny.

In our epoch, the slogan “Chess and checkers to the masses as a weapon of cultural revolution” has been expanded: “Imbue chess and checkers with political content, make our chess and checkers players into political workers, conscientious fighters, conscientious participants of socialistic building.

The issue of imbuing chess/checkers organizations with politics should be understood in this way: from some, we should demand that they, being organizers, being administrators, being responsible for political issues, pay much attention to political work; and we should get the others more involved in political life, make then conscientious participants of socialistic building.

I can cite a number of examples. Let’s look at the question of chess/checkers organizations’ participation in udarnik movement and socialistic competition. When you demand that the workers of this factory or that, in addition to being members of chess/checkers team, be udarniks and set high goals for themselves in socialistic competitions, as stevedores of the Lower Volga do – the checkers-playing and chess-playing stevedores – this is the way to couple cultural work with general political work, this is political work.

And there’s another form, which we can demand from more mature members of our organization – from administrators, from organizers. We measure the level of fitness for our chess/checkers work not just by purely chess/checkers talent and ability, but also by the ability to perform political and organizational work and the level of clear understanding of general political issues in our life and the imbuing of chess/checkers organizations’ work with political content.”

According to chess historian Terje Kristiansen, the above photo likely depicts “the so-called Lenin’s corner (aka Lenin’s room, Red Corner, the center of culture). Most factories and institutions had one, where pupils, students or workers met to read, chat, and play chess.” Kristiansen asked a Ukrainian-Russian friend and his Russian girlfriend about the photo. Both are now in their seventies, and are familiar with the history of chess in the Union. He shared their thoughts:

[The photo] captures the moment of the women’s chess and checkers circle. True, judging by the postures of women, by the expression of their faces and during the game on the checkerboards, the whole photo looks like a staged one (or women are just learning to play checkers and chess). You cannot see the enthusiasm and focus on the faces of the players. The two men in military uniform in the background are unlikely to be security guards. And what are they to protect here? This is clearly not a prison or a colony. Most likely, these are either the leaders of the circle, or the administrative workers of the institution (possibly the workers’ Club). In those years, many men, especially those who went through military operations, wore out military clothes (they simply did not have another). But, despite the staged plot of the photograph, I believe that it reflects the reality of that time.

A women’s championship was held in Leningrad in 1936. The next year, the section published a “Unified Checkers Code of the USSR,” providing a comprehensive set of rules for both Russian checkers (8 x 8 squares) and international checkers (10 x 10 squares).

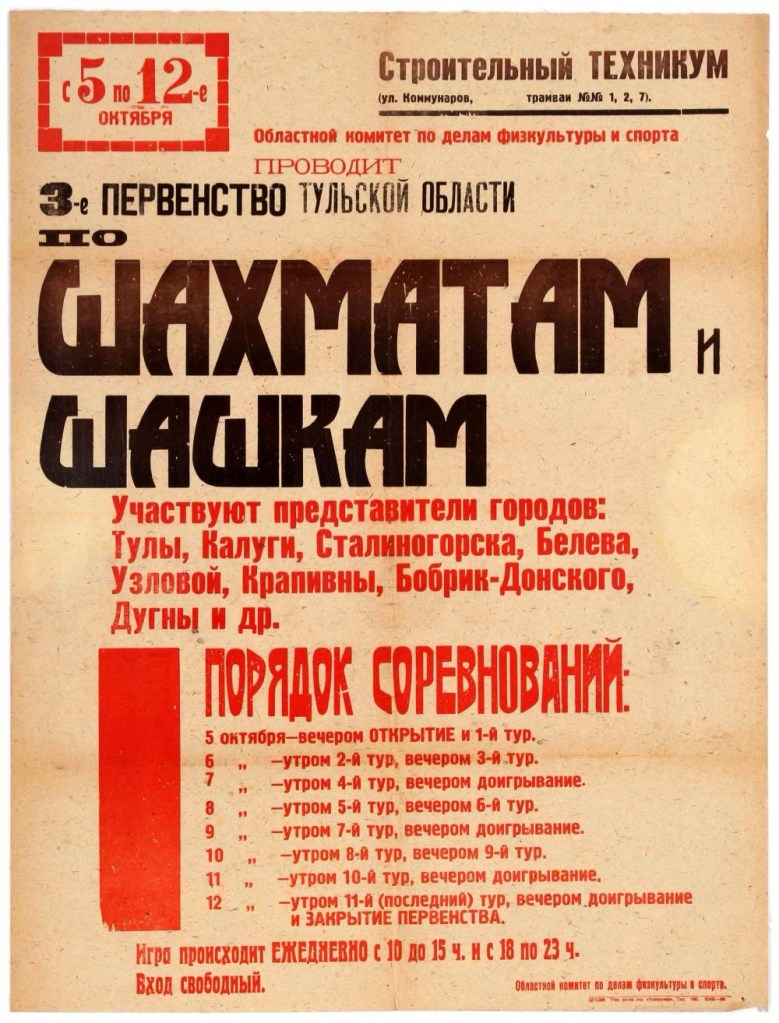

Checkers tournaments were held all over the Union, often in conjunction with chess tournaments. Here are several posters advertising such events.

Promoted and funded by the state, the number of Soviet checkers players in the Soviet Union surpassed 100,000 by the time of the fascist invasion, rising to 1.2 million by 1960. In fact, Selenkova claims that checkers temporarily surpassed chess in popularity after the Great Patriotic War, only to fall behind again following Mikhail Botvinnik’s ascension to World Chess Champion in 1948. https://www.sports.ru/others/blogs/2699763.html

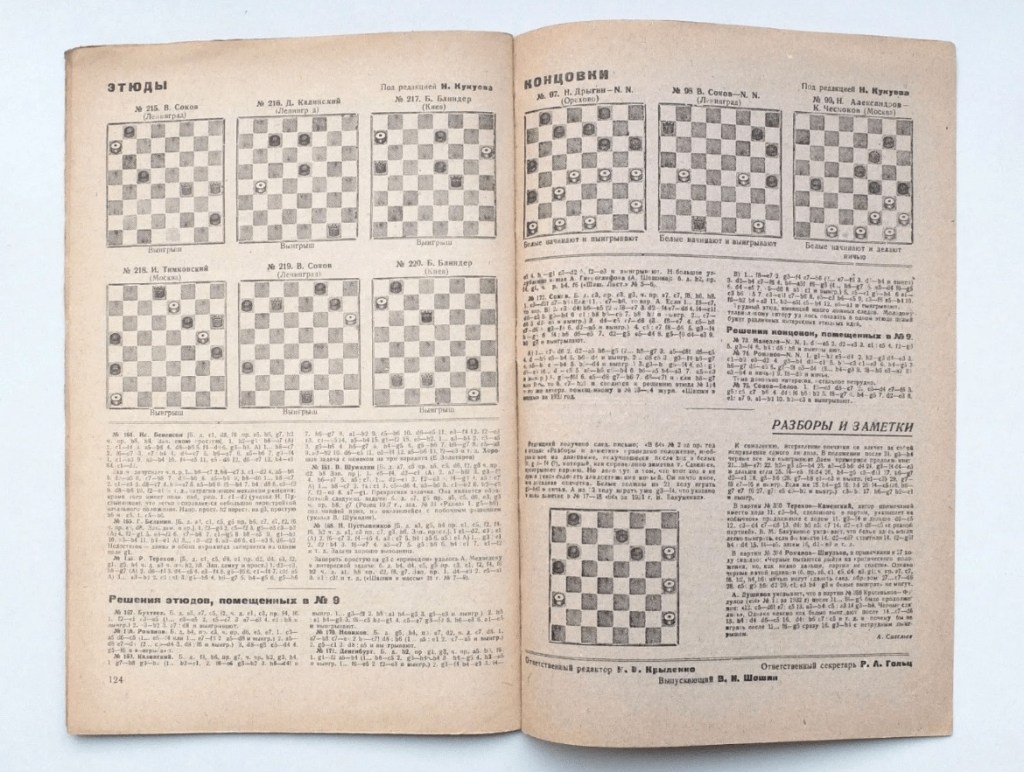

One way the Soviet state promoted chess and checkers was by publishing periodicals about them, reporting on events and presenting annotated games of instructional value. As important a chess publication as 64 carried a regular section for checkers. Here is an example:

In the early 1950s, chess and checkers formed separate sections. By the end of the decade, checkers had developed its own federation. The USSR gained its first world champion in checkers, Iser Kuperman, in 1958. Of course, the 10 x 10 international version was played.

Checkers had several advantages over chess as a means of cultural enrichment. It was a much simpler game. It could be learned and played more quickly. Vodka consumption would not degrade the level of play to the same extent as in chess. While it was played on the same 8 x 8 boards as chess, the pieces were much simpler to produce, and therefore much cheaper and affordable.

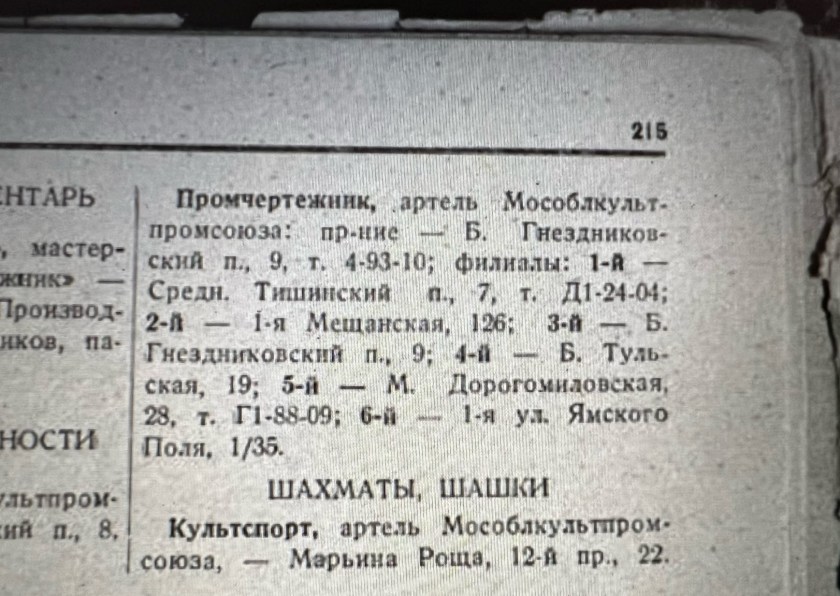

Makers of chess sets also manufactured checkers equipment. Here is a listing in the 1936 Moscow Directory for the well-known manufacturer of chess equipment, Artel Kultsport. Kultsport also advertised the sale of checkers (“шашки”) equipment.

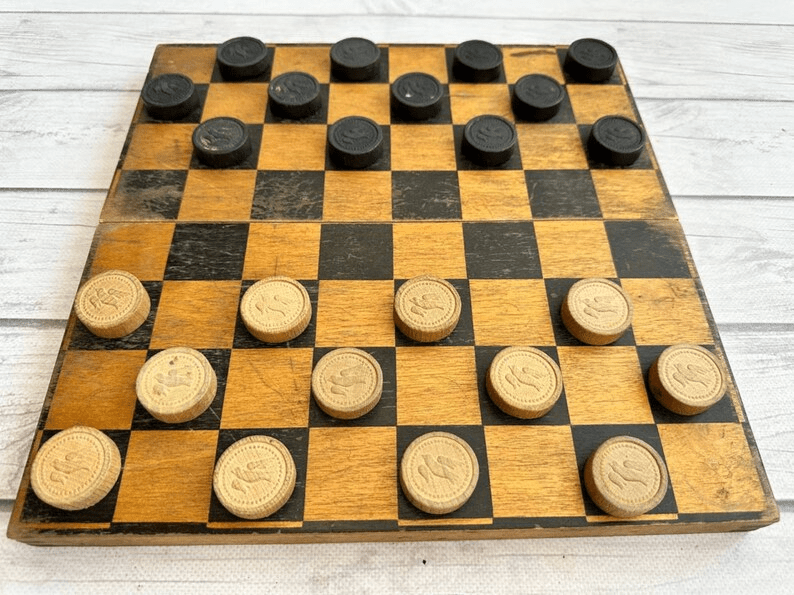

Checkers are much simpler in design than chess pieces, and accordingly are simpler and cheaper to produce. Earlier checkers were made of wood. In the fifties, plastic pieces appeared, and soon became common.

Whereas chess pieces are not susceptible to over political messaging, checkers were not so limited. It was not uncommon for them to contain Agiprop messaging, thereby undertaking the political purpose Krylenko envisioned. A case in point is this set from the 1920s.

According to Russia Chess House,

The figures depict a sickle and hammer, a star, and also a flag with the inscription “Proletarians of all countries unite”[They] are an example of agitational art of the pre-war Soviet period. There was a propaganda plan, according to which the symbols of the new government should be placed everywhere. Even matchboxes and plates had to tell the people about the accomplishments of the revolution. Utilitarian and decorative objects were to be accompanied by revolutionary slogans.”

http://chessm.com/catalog/show/5213

Some checkers contained political symbols without political slogans. Here is an example from the 1940s, where the Soviet five-point star is embossed on the wooden checkers. In Soviet heraldry, the five-point star is the symbol of the Red Army. By one account, this came about through an exchange between Krylenko and Leon Trotsky.

Another claimed origin for the red star relates to an alleged encounter between Leon Trotsky and Nikolai Krylenko. Krylenko, an Esperantist, wore a green-star lapel badge; Trotsky inquired as to its meaning and received an explanation that each arm of the star represented one of the five traditional continents. On hearing that, Trotsky specified that soldiers of the Red Army should wear a similar red star.

Not all the political icons carried by checkers were so bellicose. For example, these checkers (above) of the 1950s were embossed with the dove of peace. And the Bakelite checkers (below) celebrated the 1980 Moscow Olympics, which bore images of the different areas of competition.

Conclusion

As it did with chess, the Soviet state promoted checkers as part of its program to elevate the cultural level of the masses and to parlay the game into a means of political organizing.

Cover photo credit: USSRovskyVintage